Finding Common Ground with Hidden Figures

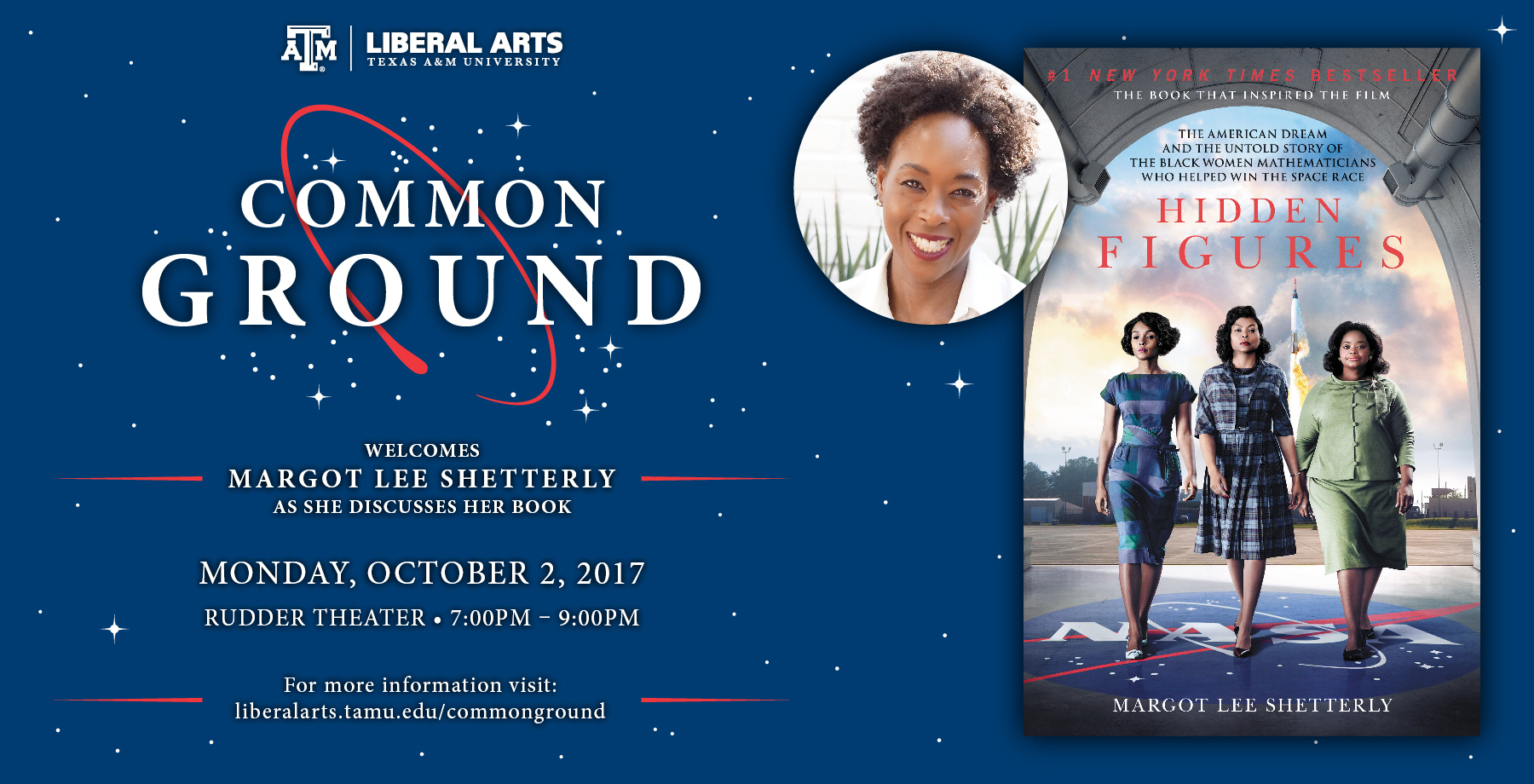

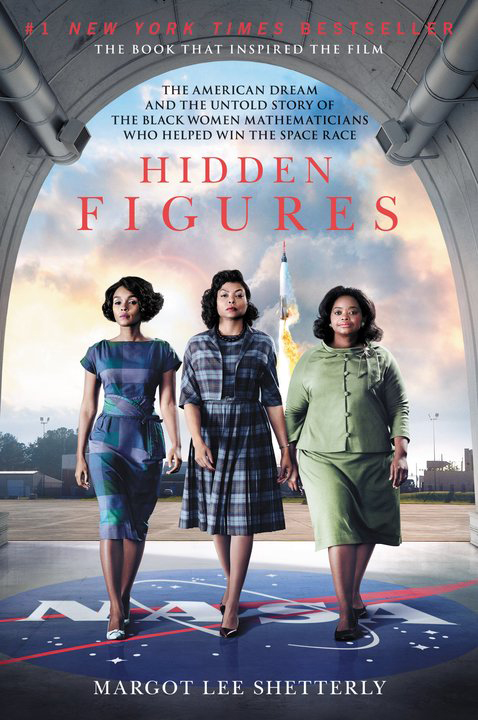

Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures: The Untold Story of the Black Women Who Helped Win the Space Race, will speak as part of the 2017 Common Ground Reading Initiative.

by Heather Rodriguez ’04

The College of Liberal Arts proudly welcomes Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures: The Untold Story of the Black Women Who Helped Win the Space Race, to speak as part of the 2017 Common Ground Reading Initiative on October 2 at Rudder Theater. The event begins at 7:00 p.m.

Shetterly will discuss her book with incoming freshmen in an effort to engage students in thought-provoking reflection and discussion. Hidden Figures celebrates innovation, encourages critical thinking, and promotes inclusiveness—which are all priorities of the College of Liberal Arts. Shetterly’s insight will show our Liberal Arts community why the college builds learning environments upon a foundation of these priorities.

This true story is set against the backdrop of WWII and the Civil Rights Era and focuses on the NASA contributions made by Mary Jackson, Dorothy Vaughan, Katherine Johnson, and Christine Darden.

Shetterly is also the founder of the Human Computer Project, a “virtual museum” of women who worked as mathematicians and engineers in the space program from 1935 onward. The project is attempting to rewrite the narrative of women in science, creating a dialogue that includes and honors the black women in the early days of NASA, as well as create a data set that can be used to recruit more women and minorities into STEM.

Shetterly discussed her book with college staff writer Heather Rodriguez.

HR: Explain the significance of the book title, “Hidden Figures.”

MS: Hidden Figures is a title that’s rich with meaning. It refers both to the women themselves, who were doing this work for many years and people didn’t see them; and it refers to the mathematics conducted by the women. There were parts of this whole endeavor of the space program that were very high-profile like the astronauts, test pilots, and Mission Control; but we didn’t really understand how much work went on behind-the-scenes to make that successful. These women were very much part of that. Their numbers were the bedrock of so much of the work that was done in American aeronautics in the 19th century.

HR: How did you first hear about these women?

MS: I grew up in Hampton, Virginia, where my dad was a research scientist for NASA. These women were part of my community. They were my parents’ friends; they were people from church. But it wasn’t until I started the book I could say I really knew them or their professional lives.

HR: Why did you choose to focus on these four women in particular?

MS: There were scores of black women I could choose from, but what I wanted were women who’d spent their entire careers at Langley [Air Force Base], so I could paint a full picture. I wanted women who had notable careers, who had really accomplished something interesting. For example, Mary Jackson was the first black woman to be promoted to engineer at NASA in 1958, at a time when very few women of any background were engineers. Dorothy Vaughan was the first black supervisor. Katherine Johnson recently received the 2016 Presidential Medal of Freedom for her calculations for the trajectories of the Mercury Project. And Christine Darden, who was the baby of the four, went on to become a world-renown expert on supersonic flight and sonic phenomenon. She really did stand on the shoulders of the other women and achieved a tremendous amount of success.

All of their lives intersected in many ways through big picture events like WWII and the push for desegregating Virginia schools, so having those coincidences in their lives made the story mature.

HR: How were these women’s legacies able to survive when they were largely unknown until now?

MS: The fact is, there’s quite a bit of documentary evidence in employee newsletters and personnel files, or the Norfolk Journal and Guide, which is a black newspaper in southeast Virginia. But there was also word-of-mouth. I was able to interview Katherine Johnson and her children, and I interviewed the children of the women who’d passed away.

HR: Why do you think they were so unknown in the world at-large?

MS: I think that every story has its time. These women didn’t know they were making history; they were just living their lives. They were going to work, taking care of their families, going to church on the weekends, they were Girl Scout leaders. They had all of these unique parts of their identities. But I think that every story has a time, and, for many reasons, the story of these women and their lives is now.

HR: One of the college’s priorities is creating an inclusive environment. Do you believe this book will help enforce this?

MS: I really hope so. I love big sweeping American stories, and I love big adventures. I wanted these black women to get their adventure. There are so many stories out there that are grand and sweeping or even quiet and interesting, and it’s incumbent upon those of us close to these stories to tell them. I’m really close to this story—it’s personal and meaningful for me. And, in many ways, I think I’ve been trying to express my whole life how to manage multiple identities of being black and female and professional and American and southern

Hopefully, this book will show a story many people know, with protagonists they may not have expected. They’ll see it as so American. And maybe people will think, “Hey, I have a story too! It’s another amazing story, and I’m the one to tell it, not anyone else!” I hope that happens.