Why the Pulitzer Prize committee keeps ignoring women’s history

Women's work hasn't been hidden. It just hasn't been seen.

by Elizabeth Cobbs

In its first 100 years, the Pulitzer Prize committee recognized a book focused on women’s history only once.

And that was a book about childbearing.

Today, the 101st winner took its place on the shelf of great American books. The prize committee stuck to its tradition.

Women sit on the Pulitzer jury. I myself participated in 2008. Eight prizewinners have been women. Why, then, is the story of women nearly blank?

The problem stems from the misconception that female achievement is peripheral to the American story. When I decided to research the nation’s first female soldiers, a friend previously on the Pulitzer jury questioned whether I could make a “whole book” out of it. His comment echoed an editor who warned another historian writing a book on the Progressive Era that the inclusion of female leaders weakened the story line.

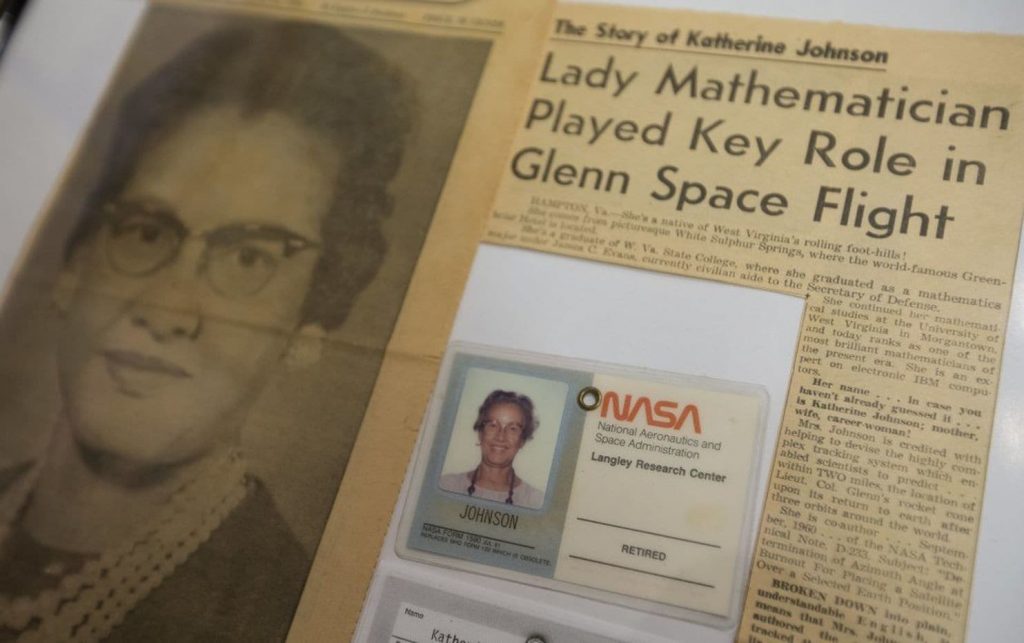

Yet as the film “Hidden Figures” illustrated so powerfully two years ago, women have long played notable roles. The African American women who served NASA pulled up to the building in their wide-bodied automobiles, walked through the front door and lined up on the tarmac to shake hands with astronauts whom they had helped put into space. No one dipped behind a potted palm. None covered her face with an apron.

Women weren’t hidden. They just weren’t seen.

It’s an old story. One-hundred years ago, American telephone operators served in both major offensives that the United States fought during World War I. Gen. John Pershing trusted only women to handle tactical communications near the front line. Commands to advance or retreat, fire or cease firing, were delivered by telephone. It took male soldiers approximately 60 seconds to connect a call; it took women only 10. In wartime, the waste of 50 seconds spelled death.

Archival film footage recently released by the National Archives shows U.S. soldiers lining up after the armistice for Pershing’s review at Chaumont, France. Thousands of troops straightened their shoulders, tucked in their bellies and snapped to attention as the charismatic general looked out upon the sea of officers and other men who served him, their country and the cause of world peace. Female Signal Corps soldiers stood in the front row, in plain view, proudly wearing their blue Army uniforms, brass insignia and aluminum dog tags.

Because of their role in logistics, women stayed in uniform longer than most men, some remaining in service until 1920. Altogether, 223 women served in France, some near the front, most well behind the lines. The United States became the first modern nation to induct women.

The operators’ 25-year-old leader, a graduate of New York’s Barnard College, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. Grace Banker, of Passaic, N.J., was one of only 18 Signal Corps officers selected out of 16,000 eligible soldiers. The medal honored her “untiring devotion” in a position of great responsibility to “assure the success” of the Army at Verdun in the Battle of Meuse-Argonne.

When Banker returned home, however, she and other women found themselves persona non grata. The Army refused to recognize their military service. Men who had stood beside them on the parade ground in France received Victory Medals, federal and state bonuses, hospitalization for disability and military burials.

The women received nothing.

Psychologists use the term confirmation bias to describe the human propensity to ignore data that does not conform to preconceptions. If we don’t believe black women belonged in the space program, we don’t see them. If women don’t fit our image of soldiers, we don’t remember them in the front row. If we think women played second fiddle in the United States’ political development, we don’t research their impact. As long as scholars view women as secondary, facts that don’t fit this assumption will be overlooked. The conviction will be reinforced that women’s stories cannot reveal something essential about the American experience.

A granddaughter of one of the World War I veterans recently told me that she’d never understood her grandmother’s framed citation for “exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous service” at the battle of St. Mihiel. With little mention of women in textbooks that discuss the war, this proof of valor was mystifying rather than meaningful. Lacking context, the fact’s relevance was lost.

As a former member of a Pulitzer jury, I’m as much to blame for the problem as anyone. Generations of jurors have selected books in which women add to the story without being the story. Women aren’t considered significant enough for a starring role. The late historian Carl Degler won a Pulitzer not for his pathbreaking book on women’s history but for his book on racial identity. David M. Kennedy won not for his book on Margaret Sanger, but for his book on Franklin D. Roosevelt.

It’s time to acknowledge and reveal women’s full impact on U.S. history. Recent bestsellers like Kate Moore’s “Radium Girls” and Liza Mundy’s “Code Girls” show there’s a whole world we’ve been missing.

This year’s winner Jack Davis fully earned the honor. In the future, one hopes the jury will also honor that half of America that has gone unheard.

This piece has been updated.

Originally posted here.