Vaccinating the Economy

Economic professors from the College of Liberal Arts explain effects of COVID-19 vaccines on the economy and what they mean for the future.

Mia Mercer ‘23

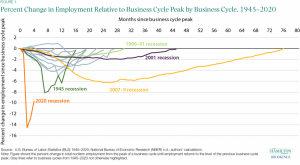

This graph from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics supports Jansen’s observation that the 2020 recession was the worst we’ve had to date. However, due to the release of the vaccine, the economy is on its way back up towards normalcy.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research in February 2020, United States employment and gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of 2019 were at the highest recorded level since 1854. Less than two months later, with the official announcement of the coronavirus pandemic, employment declined 85 percent and GDP to 90 percent, shutting down the economy and causing the unemployment rate to skyrocket. Since the initial outbreak, scientists, economists, and politicians have been working around the clock to find ways to boost the economy. On December 11, 2020, a collective sense of hope and relief passed through these groups as the first wave of COVID-19 vaccines was released to the public.

Since its release date, the vaccine has boosted the economy, allowing people to engage safely in pre-COVID activities, and helping GDP and employment levels rise. According to economics professors from the College of Liberal Arts, the release of this vaccine is the most important step towards helping the economy heal and return to what it was prior to the pandemic.

“Vaccines are absolutely, 100 percent the answer to economic challenges imposed by the pandemic,” economics professor Jonathan Meer said. “The only way to get back to normal life, to have people doing the things they want to do, spending money on the things they want to spend money on, to have businesses being able to hire the way they want and serve people the way they want, is with vaccines.”

The recession that immediately followed the outbreak of the pandemic was the worst ever recorded in post-World War II history, with real GDP falling about 10 percent. However, in just six months following the recession, real GDP rose to be just 4 percent below that previous peak.

“It doesn’t sound like much, but 4 percent is still a pretty big recession, since it’s about two years of typical growth,” economics professor Dennis Jansen explained. “If we were just growing at our usual rate, it would take us two years to get us back to where we were a year ago from where we are now.”

But according to Jansen, the vaccine accelerates economic growth because it encourages the public to return to normal behavior.

“There’s a release by the International Monetary Fund forecasting GDP growth, and in January they thought GDP growth for this year would be around 5 percent. That’s a lot,” Jansen said. “But on April 6, they released a new forecast and predicted it was going to grow 6.4 percent, and that’s because of the vaccine and increased vaccinations.”

One of the main reasons why the vaccine has been so beneficial to the economy is it’s allowing people to feel safer. According to Meer, more people are starting to resume their pre-COVID activities after receiving the vaccine, which is helping businesses like the airline industry, recover.

Not only has the vaccine aided in the rising real GDP levels, but the vaccine has stimulated the economy in other ways, helping businesses to open up, travel to increase, and increase the number of people who feel safe enough to resume normal everyday activities.

“Continued vaccination efforts will influence the economy moving forward because people are feeling safe enough to do what they did before the pandemic,” Meer shared. “There are two potentially positive spillover effects of this pandemic on the economy: One, the realization that some jobs can be done from home, which would save everyone a lot of money and make people happier; and two, hopefully, people will wear a mask and stay home when they’re sick.”

Along with the vaccine, other factors that contribute to the rise in economic activity are government-issued stimulus checks being distributed in the hopes of goading individuals to increase economic activity. Due to these stimulus checks and since the beginning of the pandemic, personal income in the aggregate is up.

“During a recession, people get laid off, they quit working, they have less money, personal income falls. It certainly doesn’t rise, because people have less money,” Jansen said. “However, this recession is different. On average, personal income in this recession has gone up and it’s gone up with these checks being mailed out. The other thing that’s gone up is personal savings. So people get these checks and they count as income, and on average, they don’t spend them. This too will contribute to the recovery and return of economic activity as it was in the past since there could be a big burst of spending or inflation due to the money that some people are sitting on.”

According to both sources, it’s important to understand the influence of the pandemic on our economy in case it happens again. Meer suggests one of the things we’ve learned is that there is almost no sum of money too great to spend on ending the pandemic once it has begun, which also suggests we should be investing enormous amounts of money to prepare ourselves for future pandemics.

“We’re going to learn how effective or ineffective our various policies are that we pursue during this time,” Jansen shared. “It’s hard to tease out the effects of these policies because we’re basically enacting all kinds of things from mailing checks to having fed policies and we did them all nearly simultaneously all while we’re facing this novel pandemic. We’ll learn something about how the economy responds just as the public health people learn how the virus can be contained or not contained by various public health policies.”