Sugar Skulls Are Not Halloween Candy

Objects and traditions that originate from Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, are commonly mislabeled as Halloween decorations due to commercialism. Faculty from the College of Liberal Arts explore the history, traditions, and importance of this annual event.

By Tiarra Drisker ‘25

As Halloween approaches, some may be tempted to paint skeletons on their faces and feast on sugar skulls and pan de muertos. These traditions may be fun to participate in, but Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a holiday with significant cultural importance to Mexican heritage that predates Halloween.

Día de los Muertos is a Mexican holiday where the souls of those who have passed come back to visit their loved ones. Families prepare food, drink, and celebrate the lives of their deceased friends and relatives. Though the holiday is celebrated Nov. 1 through Nov. 2, Nov. 1 is dedicated to the children who have died and Nov. 2 is dedicated to all adults who have died. Day of the Dead has many symbolic foods and traditions, but the commercialization of these sentimental symbols cheapens their meaning.

“It is a way to honor those who have passed but it’s not a day to mourn,” Sonia Hernandez, an associate professor in the Department of History, shared. “It’s a time to celebrate those who have passed on and to receive them. As per tradition, it’s the only time that the portal to the Land of the Dead is opened up and loved ones are able to visit us. Even if it is about death, it is very much about celebrating the life of those who are no longer with us.”

“It is a way to honor those who have passed but it’s not a day to mourn,” Sonia Hernandez, an associate professor in the Department of History, shared. “It’s a time to celebrate those who have passed on and to receive them. As per tradition, it’s the only time that the portal to the Land of the Dead is opened up and loved ones are able to visit us. Even if it is about death, it is very much about celebrating the life of those who are no longer with us.”

There’s much more to this vibrant holiday than its food and lively celebrations. The Day of the Dead originated roughly 3,000 years ago in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Its traditions stem from Mesoamerican ritual, European religion, and Spanish culture.

“The sugar skulls find their roots in the ancient Aztec tradition of building altars called tzompantli using rows of actual human skulls,” Hilaire Kallendorf, a professor in the Hispanic Studies Department explained. “The Aztecs practiced human sacrifice to appease their gods. The Spaniards brought with them the technique of sweet-making called alfeñique, which uses pure cane sugar to make a soft paste which can be poured into molds or fashioned into different shapes. When the Spaniards came, they tried to suppress many native traditions such as this one, resulting in a fusion of cultures where new rituals arose to take the place of the old ones that were prohibited.”

Sugar skulls usually bear the name of the person to whom they are given. They are a form of memento mori, which is a Latin phrase meaning “reminder of death.” They remind people that the only thing certain in life is that we will die one day. The marigold, or cempasuchil in indigenous terms, is known as “the flower of the dead ” despite its bright color. It too has its own significance within the holiday.

“Since indigenous times, marigolds were planted near crops because marigolds produce a natural insecticide,” Hernandez said. “It helped to counter plagues and diseases affecting the crops. The strong aroma and the bright color are things that will help guide the souls back to their home. Not every family does this, but some families create paths from the cemeteries to their homes to guide the souls as they make their way home.”

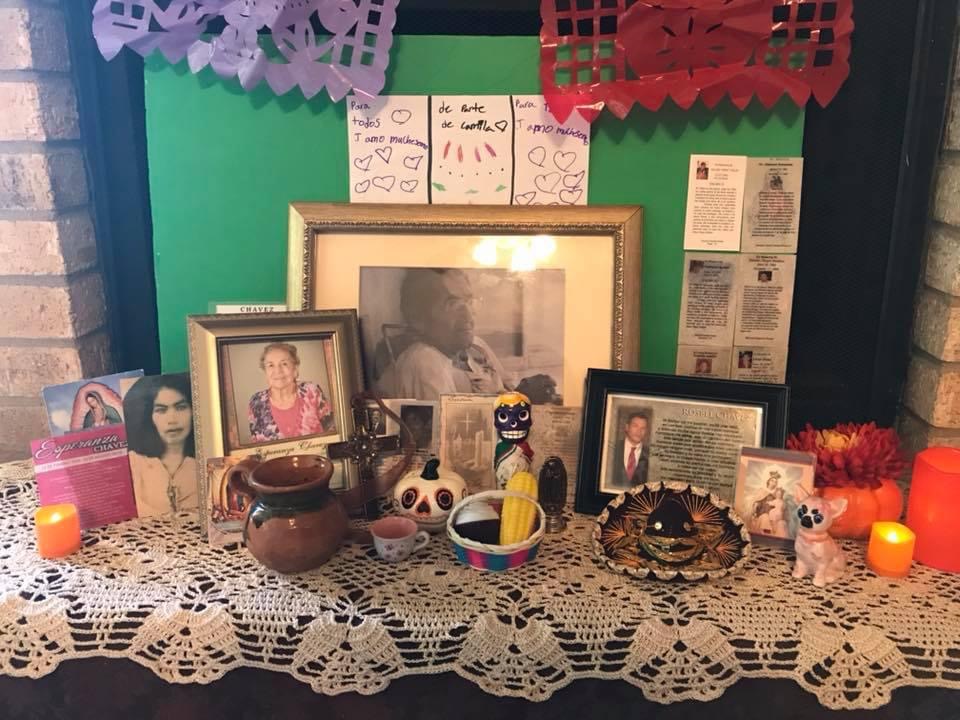

All items that families make for their deceased loved ones are then placed on an altar called an ofrenda as offerings to honor their loved ones. Ofrendas contain pictures of the deceased as well as their favorite foods or items from when they were alive. While the festivities can seem lighthearted and entertaining, people should be aware of the sentimental value Día de los Muertos, as well as its traditions, have for people of Mexican heritage. “There is no single appropriate way to celebrate Día de los Muertos, but a degree of cultural sensitivity is required,” Kallendorf said. “It doesn’t have to be solemn or deadly serious, but it does need to be respectful.”