How The US Became Independent (And Inseparable) From Great Britain

From Winston Churchill to Kate Bush, a Texas A&M historian explores the close, complicated relationship between the United States and the country we celebrate our independence from today.

By Luke Henkhaus, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications

Turn on a radio in the United Kingdom right now, and there’s a good chance you’ll hear the catchy but mournful tones of English artist Kate Bush’s 1985 hit “Running Up That Hill,” which recently topped the UK singles chart more than 30 years after the track’s initial release, thanks to its use in the latest season of the American TV show “Stranger Things.”

The song’s resurgent popularity on both sides of the pond is just the latest reminder that while the U.S. may have declared its independence from Great Britain 246 years ago today, the two nations have managed to stay remarkably close — not only culturally, but economically and strategically too, says Texas A&M University history professor Troy Bickham.

According to Bickham, who specializes in early American history and the history of the British empire, it’s largely a history of shared interests, values and language that created the close bond between the countries today.

From Revolution To Resolution

Before he was president, John Adams served as the United States’ first ambassador to Great Britain. | Getty Images

By the time the Declaration of Independence was signed in Philadelphia, the writing was already on the wall for Britain’s relationship with its North American colonies, Bickham said. News of growing resistance across the Atlantic widely circulated in the British press for more than a decade, and by 1775, King George III had officially declared the colonies to be in a state of revolt. By the time the declaration reached his desk, he was already mobilizing troops for an assault on New York.

Though the resulting war is often viewed as a conflict between the Americans and the British, that’s not exactly how people understood it at the time, according to Bickham. Early on, it was widely understood not as a revolutionary war, but as a kind of civil war within the British Empire.

“The term ‘American’ to describe Americans was only then emerging to apply to people who were not indigenous,” Bickham said. “George Washington would have described himself as an Englishman, as would Benjamin Franklin and everyone else. What they were disagreeing over was what it meant to be an Englishman.”

Back in Britain, large swaths of the population were sympathetic to the rebelling colonists’ cause, and the idea of waging war on them made many uneasy. High-ranking military officers resigned in protest, and others complained loudly in the press and in the House of Commons.

“It was a huge issue, it was divisive,” Bickham said. “Until the 1930s, the largest peace petitioning movement in British history was to stop the war with the colonies. … One newspaper refused to distinguish between the British and American dead, saying ‘they’re all sons of Britain.’”

Arguments against the war were often framed in terms of practical and economic concerns — partly because voicing full-throated support for American independence would be grounds for treason, Bickham said. And as the war dragged on and became an increasingly costly endeavor, those arguments only got more persuasive.

“They would say, ‘Practically this doesn’t make sense — we should be trading, not killing,’” Bickham said. “Eventually, a bill came up for funding for the war for the next year and Parliament said, ‘You know what, this is too expensive, we’re not winning, we’re done.’”

As British forces pulled out, governors and other colonial officials were ousted from the new United States, and many others who had been loyal to the crown left voluntarily, Bickham said. However, the former loyalists who chose to stay found that they were largely allowed to live their lives and go about their business undisturbed.

In 1785, just two years after winning its independence, the U.S. opened up formal diplomatic relations with Britain, sending John Adams across the Atlantic for an audience with King George.

“Adams leaves that meeting having come to the conclusion that, to some extent, the United States and Britain have a lot of cultural similarities that allow them to do business,” Bickham said.

Ultimately, Bickham said it didn’t take long for any lingering animosity between Britain and the U.S. to subside in favor of a mutually beneficial economic partnership. After all, Britain still had a tremendous need for American agricultural products, and its former colonists were more than happy to provide them for the right price.

Similarly, since the U.S. was still largely an agrarian society, Americans relied heavily on the more industrialized Britain for products they couldn’t produce themselves.

“The United States is Britain’s largest overseas market for goods before the revolution, and it is so after the revolution — that doesn’t change until well into the 19th century,” Bickham said. “A lot of the cotton from the south is milled in Britain. So they are very much tied to each other.”

America On The Rise

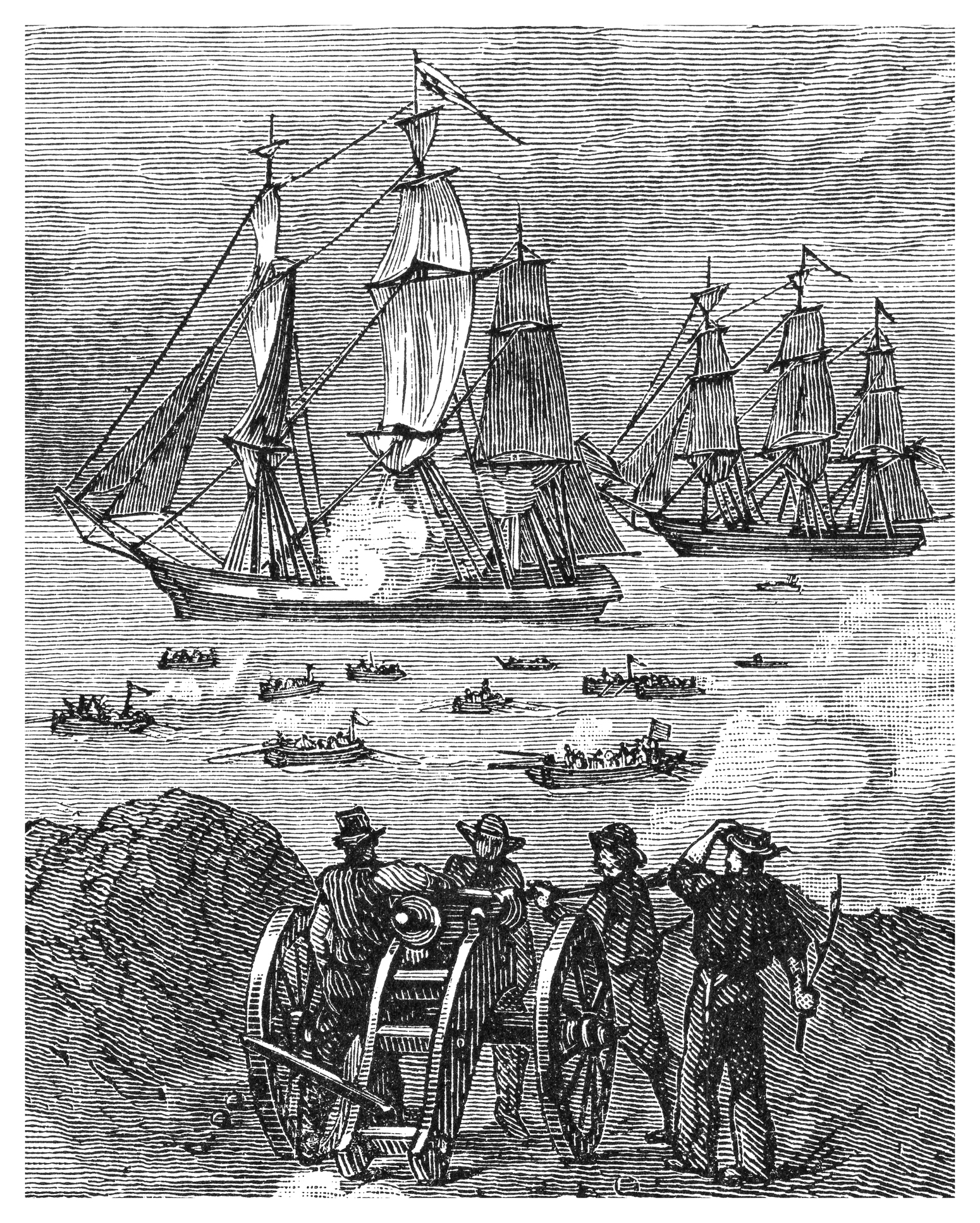

One major disruption to this harmonious financial arrangement was the War of 1812, which was sparked in part by British efforts to curtail American trade with France during the Napoleonic Wars.

An illustration of British ships bombarding the community of Stonington, Connecticut during the War of 1812. | Getty Images

Wary of British attempts to reassert power, American political leaders pushed back hard. When tensions eventually boiled over, the U.S. and Britain were at war again, though not for long this time.

“They fought a small war that lasted a couple of years, and not much came out of that except that the British recognized at the end of the war that the United States would be the preeminent power in North America,” Bickham said. “The British kind of cut their losses, kept what became Canada, but essentially recognized that the U.S. is going to do their own thing and it’s easier to make friends with them rather than fight them.”

As the decades went on, the two nations maintained strong economic ties, as well as a high degree of social and cultural cooperation, Bickham said. Abolitionists and members of various religious movements often corresponded with their counterparts across the Atlantic, and British literature remained a favorite of American readers.

“There was a substantial amount of social mixing, too,” Bickham said. “Certainly the American elite still looked to the British for legitimacy and so on.”

Further into the 19th century, ties would continue to strengthen between the American and British upper classes, as daughters of increasingly wealthy American elites would marry into noble but less-well-off British families, creating a union of social status and financial resources that suited both families’ goals.

“Winston Churchill’s mother is American, the Vanderbilts married into the aristocracy as well, so there was a lot of connection that way,” Bickham said.

The World Wars And ‘The Special Relationship’

Later on in the 20th century, it would be Churchill himself who described the U.S. and Britain’s growing bond as a “special relationship.” Though that relationship wouldn’t come to bloom until the Second World War, Bickham said the seeds were planted during World War I.

When the war broke out in Europe in 1914, there was some question as to which side the U.S. would end up on if it chose to enter the fray. German-Americans represented a larger portion of the U.S. population than any other ethnic group at that time, but the U.S. and Britain’s common language helped turn American sympathies toward the Entente Powers.

“The advantage the British have over the Germans is that British propaganda doesn’t have to be translated,” Bickham said.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill discusses tactics with American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Malta, 1945. | Getty Images

After entering the war and helping Britain and its allies secure victory, the U.S. returned to a more isolationist stance for a time, even into the initial years of WWII. But ultimately, the U.S. would turn out to support its mother nation once again, supplying the U.K. with massive shipments of military supplies before eventually mobilizing its own troops to fight side-by-side with British and other Allied forces.

That’s when “the special relationship,” a term first used by Churchill in a speech in 1946, really began to crystallize, Bickham said.

“Certainly in the wake of the Second World War, it gets very much cemented, as the British and Americans work together to rebuild Europe as western democracies and to thwart the Soviet Union and Communism together during the Cold War,” he said.

Through it all, the British and American people maintain their strong cultural affinity, as popular music, books, movies and television shows from one nation are easily exported to the other. In fact, it was during the Cold War that “Running Up That Hill” was first released and found its way to American shores.

As Bickham notes, that the song has now made its way back across the Atlantic almost 40 years later by way of a hit American TV show is just another example of the enduing connection between the two nations.

Originally published here by Texas A&M Today.