“The First Pride Was a Riot”: The 50th Anniversary of Stonewall

There's a well-known saying among the LGBTQ community: "The first Pride was a riot." We talk to history professor Terry Anderson about the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and how they shaped the modern fight for LGTBQ rights.

by Heather Rodriguez ’04

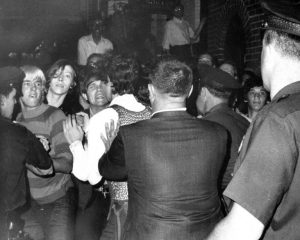

Fifty years ago, in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, the Stonewall Inn—a bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village frequented by members of the LGBTQ community—was raided by police. It wasn’t the first time the bar was raided, but it was the first time a raid did not go as planned. This time, the patrons resisted, sparking the gay liberation movement and leading to the modern fight for LGBTQ rights in the United States.

“In order to understand Stonewall we have to talk a little about the 1960s—the last great reform era in American history,” said Terry Anderson, a professor of modern United States history. “We had the Civil Rights movement attempt to overturn Jim Crow segregation, student movement against campus regulations, anti-war movement against the Vietnam War, and in September of 1968 female activists held the first march in the women’s liberation movement, protesting rules, regulations, laws and traditions that were inhibiting women’s opportunities and equality in America.”

And while the 1960s were a time of progress in the country, it was also a scary time to be a member of the LGBTQ community. Not only was non-heterosexual activity illegal in every state, but it was considered a mental illness.

“The traditional way to resolve mental illness was through electric shock treatment, and they did the same to gay people,” Anderson said. “Or they would try to give them massive amounts of medication, and some ‘experts’ advocated chemically castrating them or even giving them a lobotomy.”

Not only that, Anderson said, but people who were suspected of being gay would often lose their jobs and be dishonorably discharged from the military.

“That’s what gay people faced,” he said. “And during the 1960s we have all these movements that were a stab against the establishment. People were saying ‘We won’t take it anymore.’ Which brings me to Stonewall.”

Like many people in a marginalized community, LGBTQ people would frequent places where they felt safe and welcomed. The Stonewall Inn was one such place; there, it didn’t matter if a person was homeless, or transgender, or a person with a disability, or a person of color. People found a home there, and as a result, the bar was often targeted by police. However, officers quickly lost control of the situation on June 28, 1969.

“The police came in with their batons, and started bashing away,” Anderson said. “And these patrons have seen this before. They’ve seen it in the South, where police were bashing African Americans; they’ve seen it at Columbia University, where police beat on students. They’ve seen it in their communities as well. And this time, the people fought back.”

People began throwing things. A scuffle broke out, which escalated into violence when police roughed up a woman in handcuffs. Two transgender women of color, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, were said to have resisted arrest and thrown the first bottle at police (respectively). After the riots, the women went on to co-found the organization STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), dedicated to helping homeless young drag queens and transgender women of color. While they have passed away, their legacies continue to stand for strength, compassion, and resilience in the face of oppression.

The first night resulted in the arrest of 13 Stonewall patrons and the injury of four officers.

“News of this spread through Greenwich Village,” Anderson said. “The next night, 400 gay men and women show up. It was the physical announcement of gay liberation.”

Over the next several nights, as the riot eventually quieted down, gay activists congregated around Stonewall and built the community that would drive the LGBTQ rights movement. When it was all over, 21 people were arrested over six days, and the Stonewall Inn shut its doors for decades. The riot was over, but the fight had just begun.

“The community began to write their own underground newspapers, giving their perspective and not that of the establishment,” Anderson said. “One year later, you have the first march of the gay liberation front…and 10,000 people show up. And it spreads across the country, and it was the beginning of the Pride marches we have today.”

Anderson believes that knowing the origin of LGBTQ Pride Month is key to continue our country’s progress.

“It’s incredibly important, especially in today’s climate,” he said. “From where we were back then, we really have come so far.”