Border Ware

At Port Royal, Jamaica

Port Royal, Jamaica, was a defensive colonial port settlement, captured by the English from the Spanish in 1655. By the late 1680s, Port Royal was one of the largest English trading centers in the New World. With a population of nearly 6500 and with over 2000 buildings, it was a city unequaled in North America for economic prosperity. The success story of Port Royal, however, was destined to be very short. Around midday on June 7, 1692, the high-rolling city was devastated by a massive earthquake. The ensuing tidal wave submerged over half of its area into the Caribbean Sea, killing approximately 2000 people. Another 2000 people died from injury, sickness, and plague in the weeks following the disaster.

In 1981, Texas A&M University, in joint sponsorship with the Jamaican National Heritage Trust and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, began archaeological excavations on a portion of the submerged area of colonial Port Royal. Ten years of investigations successfully uncovered several 17th-century structures and a wide array of artifacts, such as metal, glass, and pewter objects; various types of textiles; and faunal remains and organic materials. Numerous ceramic wares were also recovered, including tin-glazed earthenwares, slipwares, stonewares, and Chinese export porcelain.

This study presents the numerous Border ware vessels that were also found. First, the history of the development of the ware, including production techniques and common Border ware vessel types, is discussed. The Port Royal Border ware assemblage is then analyzed and interpreted. A list of bibliographic sources is also provided. As with all of the artifacts recovered from the site, the presence of Border ware ceramics allows for a more holistic sense of what everyday life was like in this 17th-century English colonial port town.

HISTORY OF BORDER WARE DEVELOPMENT

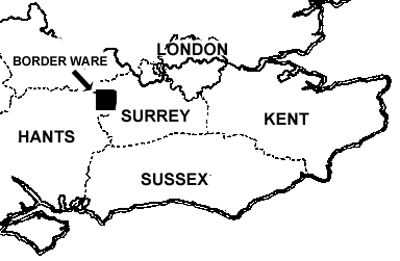

The term 'Border ware' developed as a description for the post-medieval pottery being produced in the border region between England's northeast Hampshire and western Surrey counties. The pottery being made in this region gave way, in the 14th century, to a type known as 'Coarse Border ware,' which represented a refinement of earlier ceramic traditions. The development of this Coarse Border ware was most likely influenced by migrations from the European continent, as well as burgeoning trade networks.

Coarse Border ware developed briefly in the late 15th century into a tradition termed 'Tudor Green,' the name paying homage to England's then-enthroned noble lineage. Tudor Green (examples of which are shown opposite), while distinct from what was to become classic Border ware, was likely a direct precursor, since historic and archaeological evidence has shown that both were produced in the same kilns.

During the second half of the 16th century, the Surrey-Hampshire pottery industry consolidated its hold on the London ceramics market with its fully developed Border ware, which is characterized by distinctive yellow and green glazes. It was made from local white firing clays, and its paste was coarser than the earlier fine, thin-walled Tudor Green types. It quickly became the main source of domestic pottery for the inhabitants of London and remained as such until the end of the 17th century.

There are two distinct classes of Border ware: White Border ware is characterized by a hard paste with moderate to abundant inclusions of quartz sand particles. It may also exhibit moderate amounts of reddish quartz, minor and infrequent amounts of red and/or black ironstone, and white (Muscovite) mica. Red Border ware is, as the name implies, characterized by a red or reddish brown fabric. Inclusions are similar to those found in white Border ware, except for quartz particles, which are relatively infrequent. White streaks typically found within red Border ware may provide evidence for a blending of materials. Red inclusions in white Border wares are, however, not common.

Throughout the 16th and most of the 17th centuries, white Border ware production outpaced that of red by a substantial margin. In a study of early 17th-century London assemblages, white outnumbered red by approximately 6 to 1 (Pearce 1992). While it was noted that red ware quantities increased as the century progressed, the numbers remained below that of the white variety. Red Border ware only begins to dominate London Border ware assemblages in the 18th century.

Border ware production reached its peak in the 17th century. Throughout the 17th century, and into the early 18th century, Border ware was one of the principle sources of good-quality household pottery used in London. The waning popularity of the ware, an issue inextricably entwined in the socio-economic apparatuses of the period, can be principally linked to the rise of the various Staffordshire potteries, which inspired the market collapse of white earthenware in general. Staffordshire quickly established a foothold in the London pottery market; by the mid 18th century, it was the dominant domestic ceramic producer for the city.

BORDER WARE PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES

All Border ware vessels were wheel-thrown, and some forms exhibit evidence of knife-trimming on their bases. Yellow, green, or mottled brown glaze was usually applied to one surface of the vessel. Toward the end of the 17th century, some vessel types, such as chamber pots and mugs, were glazed on both the interior and exterior surfaces.

Coarser cooking and storage vessels tended to be made of unmixed red-firing clay. Examples can be best seen in 17th-century chamber pots, as well as a select few costrels. Mixed clay was more often used for finer tablewares, such as dishes and porringers (which vary widely in their fabric matrix), and tended toward a pale fabric color.

Standard Border ware base forms generally are either flat or slightly kicked. Some forms exhibit wheel-impressed concave bases, which may have been to serve the utilitarian purpose of decreasing the amount of surface area likely to come into contact with other vessels during firing. Indeed, kiln scars left by the joining of vessels during firing are not uncommon on Border ware vessels.

Vertical looped handles were constructed principally for drinking vessels, chamber pots, certain bowl forms, chafing dishes, and candle sticks. Horizontal loop handles tend to be found on porringers but are also found on bowls, chafing dishes, and fuming pots. As is shown opposite, handles were typically attached to the body at one end and smoothed all around the joint at the other end. Wiped handles, rather than those which are thumb-impressed, are more common on all vessel forms, although thumb impressions on wiped handle-attachments may be seen on occasion.

The majority of Border ware forms are glazed on a single surface, usually the interior. Glaze was poured into a fired vessel's interior and then swirled around, often resulting in some spillage over the vessel sides. Higher quality Border wares, as well as more completely glazed forms, such as drinking vessels, were completely submerged in the glaze. Iron-rich compounds found within the glaze sometimes left dark brown or red spots, as well as occasional streaks in clear glazes on white wares and red wares (most commonly found in association with late 16th- and early 17th-century pieces). These iron marks may be within or under the glaze. By the 17th century, glazes were improved and more evenly mixed, eliminating the problem of iron staining.

To create green and brown glazes, powdered copper and manganese, respectively, were applied to a basic clear lead glaze. Brown glaze was generally relegated strictly to forms used at the table, such as mugs, bowls, and porringers. Brown was the most typical color for mugs, while green or yellow appear to be the most common colors used for all other vessel forms. Within each of the main glaze colors used, the range of hues is considerable, the end color being heavily dependent upon both the fabric color and glaze thickness. For example, depending on how thickly it is applied, clear lead glaze can appear clear, orange, olive, or brown on the red ware variety. It ranges from yellow through amber to a muted sandy shade when applied to white Border ware.

Forms with different glazes and fabrics were often fired within the same kiln. Abundant kiln scars on the forms from Port Royal attest to this practice. The orientation a given vessel assumed within a kiln may be reconstructed by the direction of the glaze run, as well as diagnostic markings left on the vessel. White Border wares, and to a lesser extent, red wares, may have lighter or darker patches in their fabric, demonstrating uneven firing.

Additional Galleries:

Examples of Border Ware Vessel Forms

Port Royal Border Ware Assemblage

BIBLIOGRAPHIC SOURCES

HAMILTON, D. L. 1992. Simon Benning, Pewterer of Port Royal. In Text-Aided Archaeology, edited by B. J. Little, pp.39-53. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

NOEL HUME, I. 1980. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

PEARCE, J. 1992. Post-Medieval Pottery in London, 1500-1700: Border Wares. HMSO, London.

THOMPSON, A., F. GREW, and J. SCHOFIELD 1984. Excavations at Aldgate, 1974. Post-Medieval Archaeology 18:1-148.

Citation Information:

2000, Barrett, Jason and Madeleine Donachie, Borderware at Port Royal Jamaica, Nautical Archaeology Program, Texas A&M University,

College Station, Texas. March 14, 2001