Hoofbeats Over the Water: INA Research on Horse-Powered Ferryboats

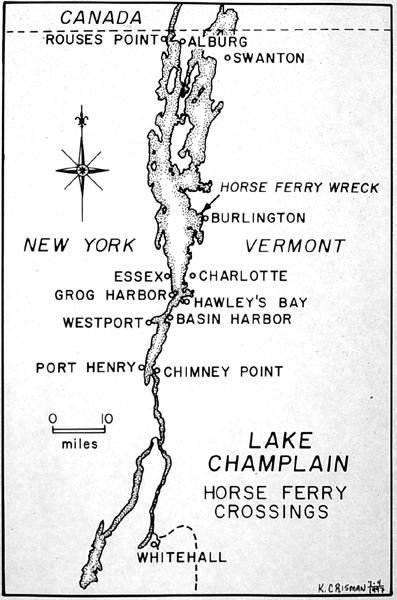

Most people are aware that mules and horses walking on tow paths pulled boats through North America’s nineteenth-century canals, but fewer know that during the same century horses also served on board paddle-powered ferryboats.

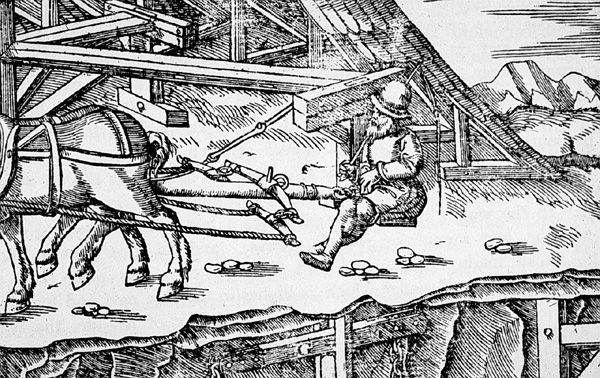

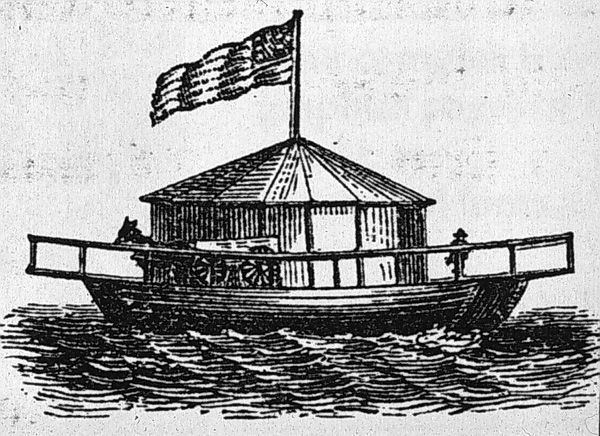

The technology that enabled ferryboat owners to harness the power of horses for boat propulsion existed for many centuries. This sixteenth-century woodcut shows the most common form of horse machinery: the horse whim. Resembling a merry-go-round, this machine had a series of radial bars to which the horses were harnessed. It was simple, reliable, and relatively efficient, but did result in dizzy horses.

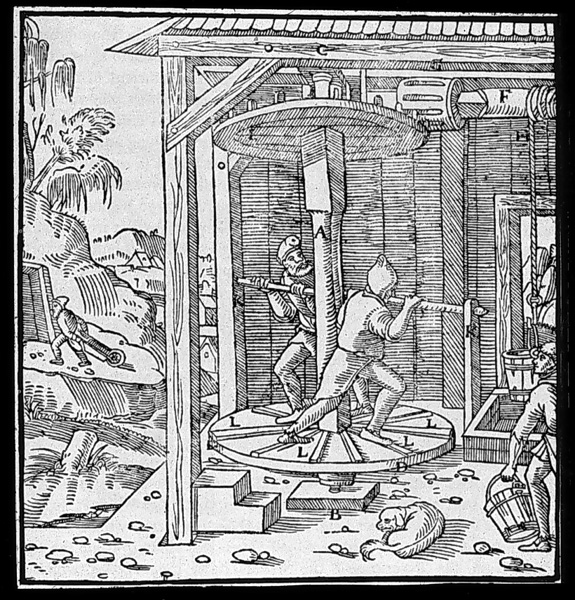

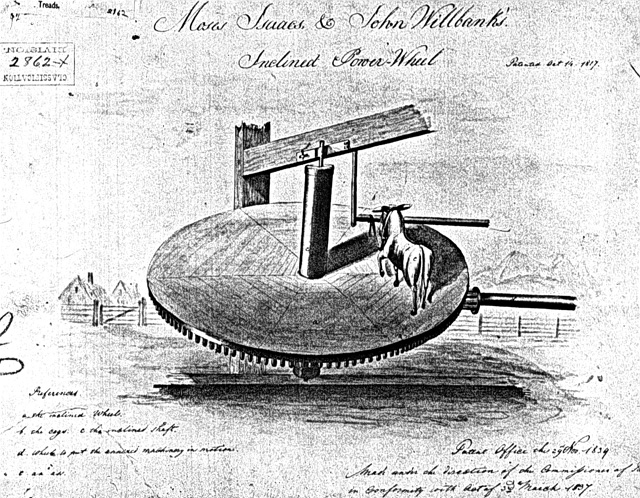

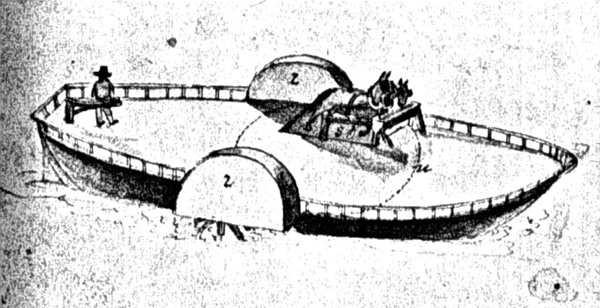

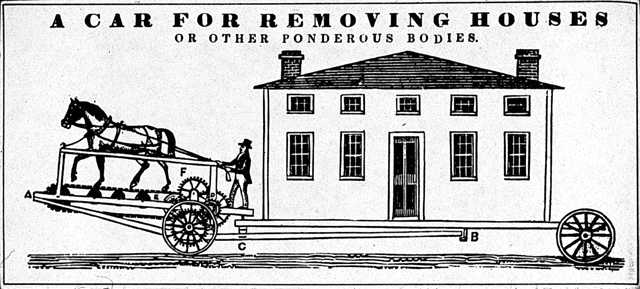

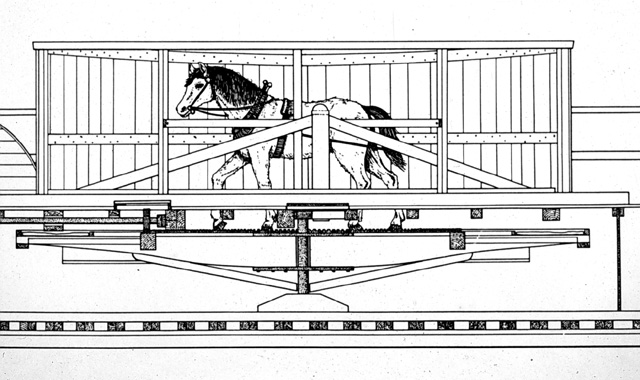

Here is another form of muscle-powered machine employed in the sixteenth century: the horizontal treadwheel. The human powerplants gripped a fixed bar and used their legs to spin the turntable under their feet. Similar versions were made for draft animals. This device will show up again in horse-powered boats in the early 1800s.

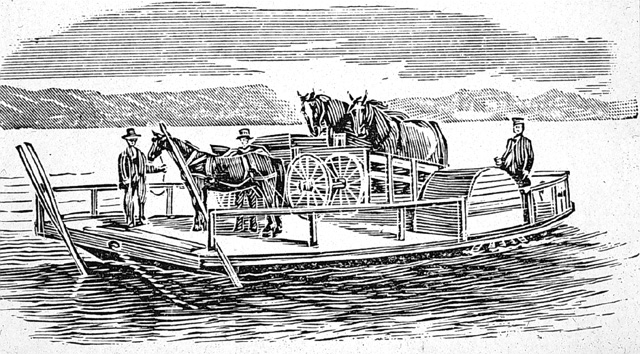

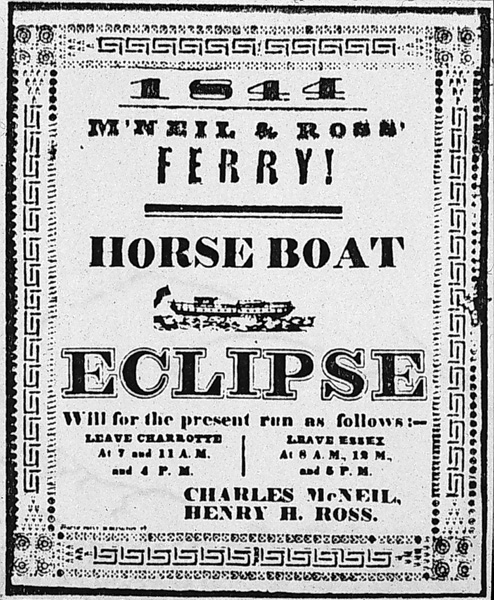

In the era pre-dating large-scale bridge construction, lakes and rivers in North America had to be crossed by some type of ferry boat, in this case a sail-propelled scow. Sail ferries were notoriously unreliable (winds often would not blow at the right time, or in the right direction), while oar-propelled ferries required expensive human labor. What was needed was some type of paddle ferry boat that combined the reliability of steam machinery with a less expensive form of power.

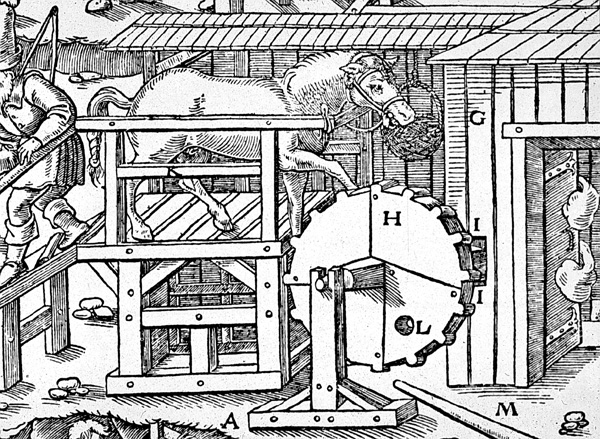

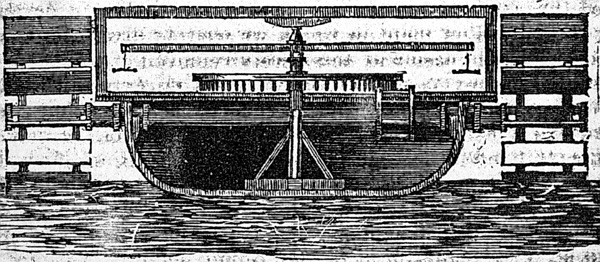

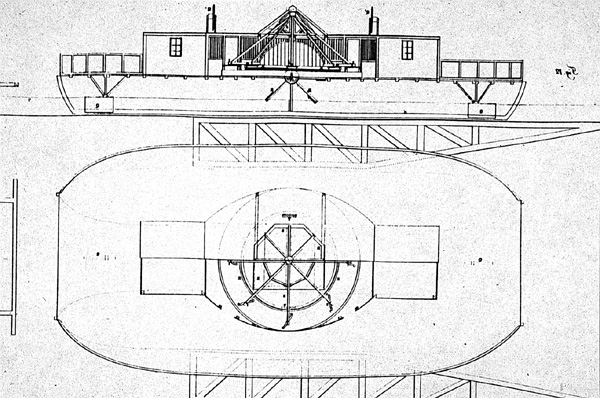

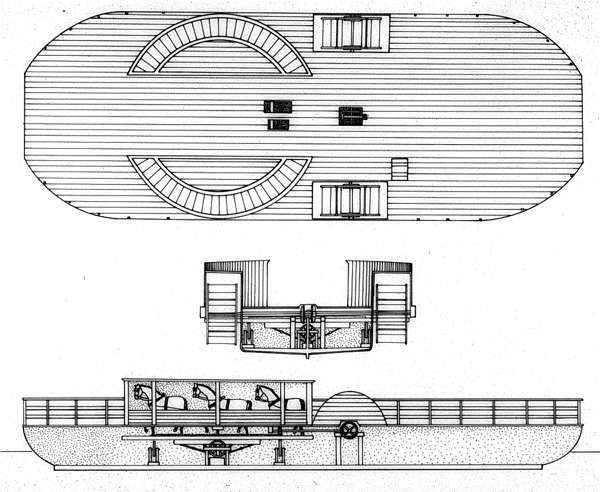

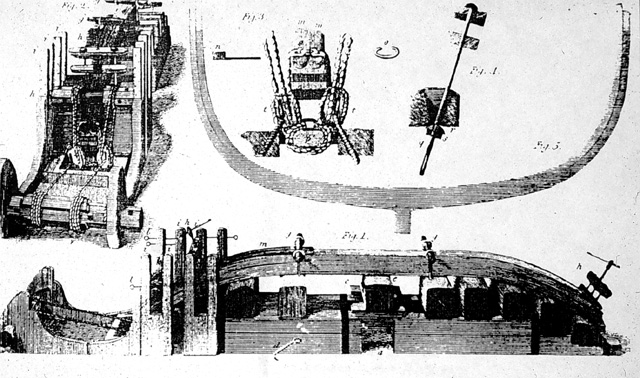

The answer to the ferryboatman’s needs appeared in 1814, when New York City ferries began employing horse-powered paddle boats. The earliest boats used the horse whim-style machinery. Because the circle for the horses required so much space on the deck it was necessary to build these ferries as twin-hulled boats or ‘catamarans.’ Plan and profile from Marestier’s Memoir on Steamboats (1824).

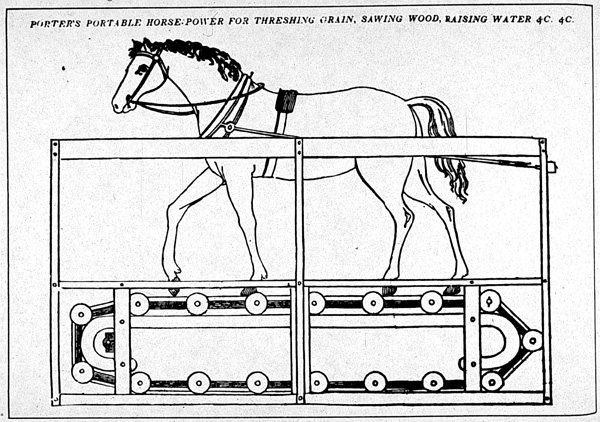

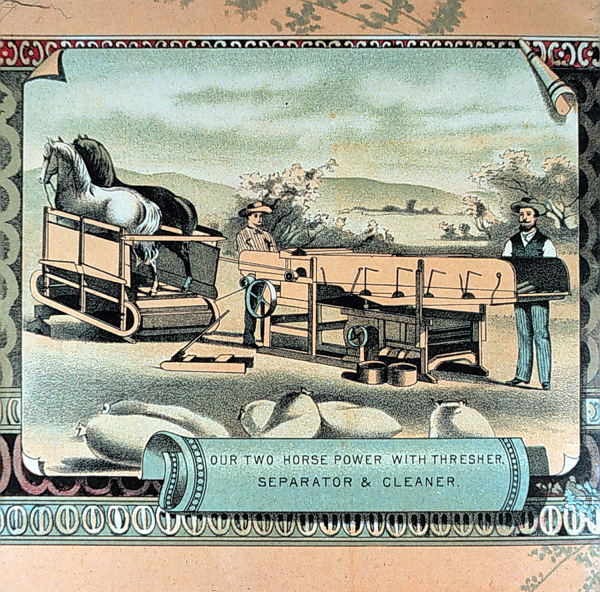

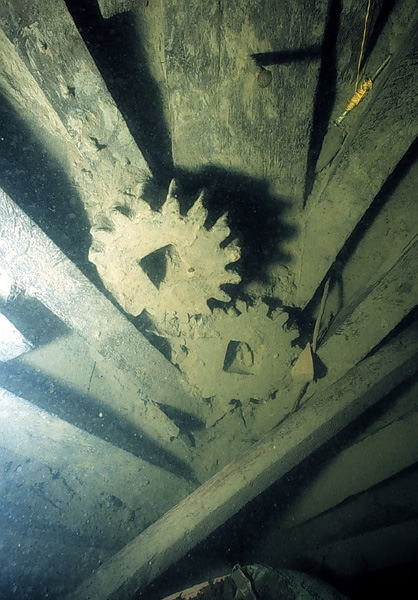

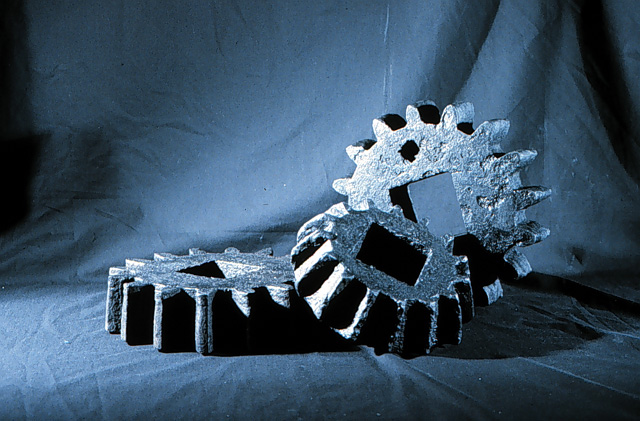

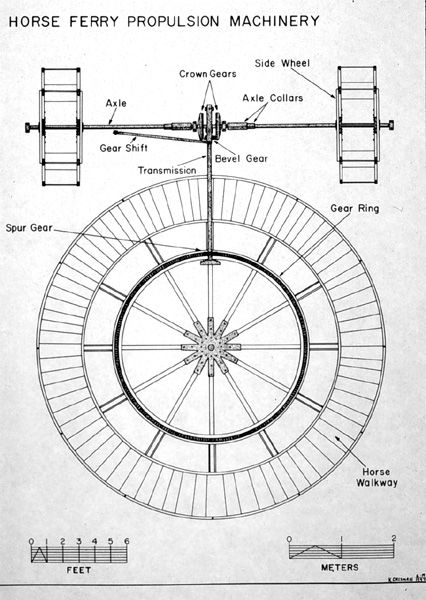

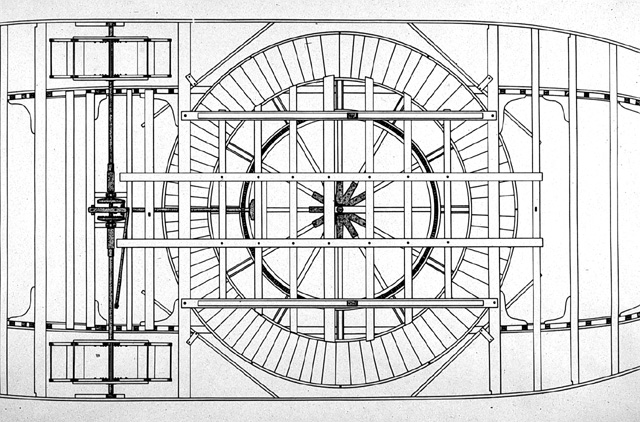

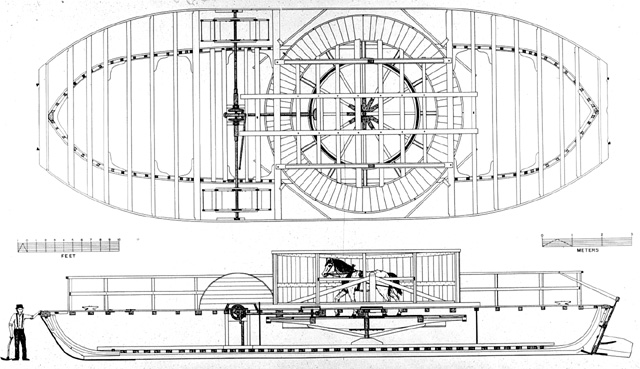

Father and son inventors Barnabus and John C. Langdon of Troy, New York patented their horizontal treadwheel boat in 1819, and for the next two decades this form of horseboat machinery would dominate the horse ferry business. By placing the wheel under the deck, and cutting an opening just large enough for the horses, the Langdons created much more usable deck space and permitted the building of single-hulled (cheaper!) horse ferries. This is a detail from one of their patent drawings.

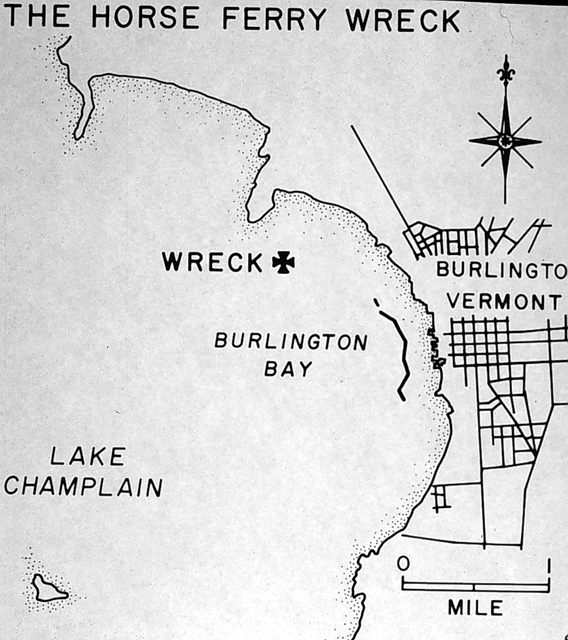

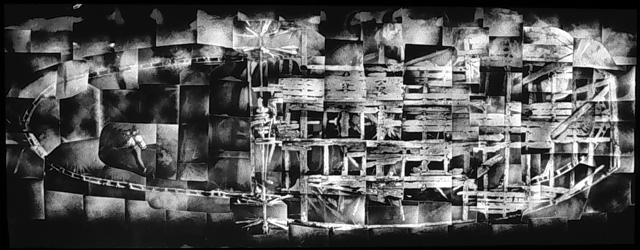

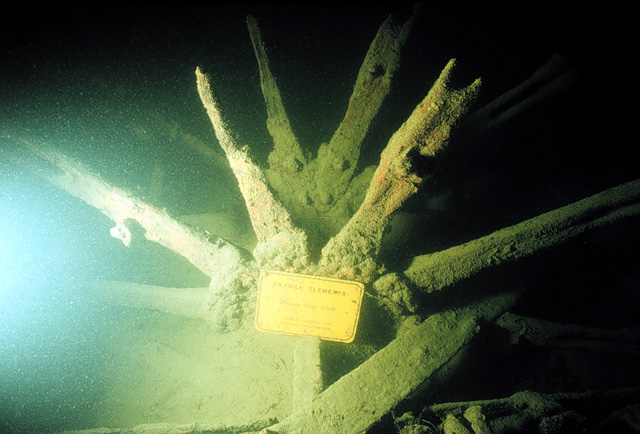

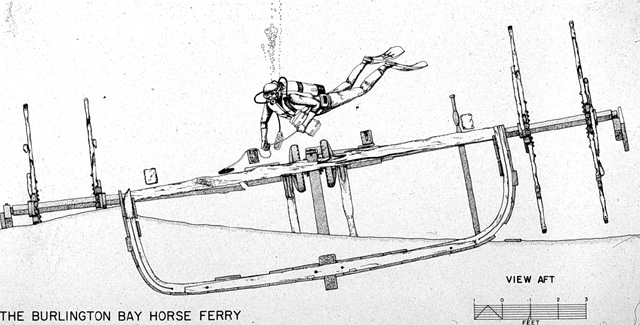

A photomosaic of the horse ferry, taken in 1984 and prepared by Scott Hill, Milton Shares, and Dennis Floss. Photo courtesy of the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation. The bow, to the left, is missing its deck, but the wreck was otherwise in good shape, and all of the machinery was found to be complete. The first of its kind every to undergo archaeological study, the wreck provided many details of horse ferry technology and operations.

The fact that the rudder was unshipped from the stern pintles and inside the hull tells us that the ferry was probably not under its own power at the time of the sinking. We believe that the ferry was at least ten years old, and possibly as many as twenty years old, at the time of sinking. Horse ferries never worked out of Burlington, so it must have been brought to this location for repairs or perhaps to sell, and then was subsequently scuttled in deep water.

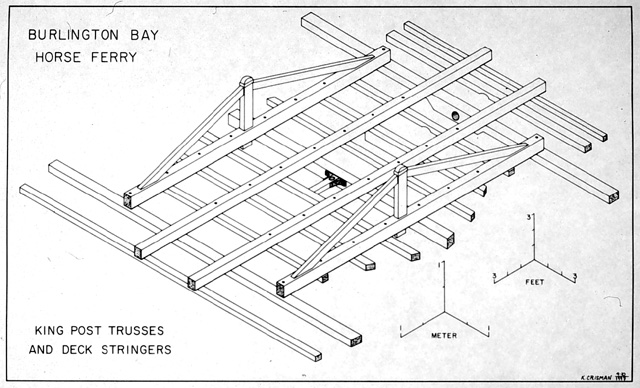

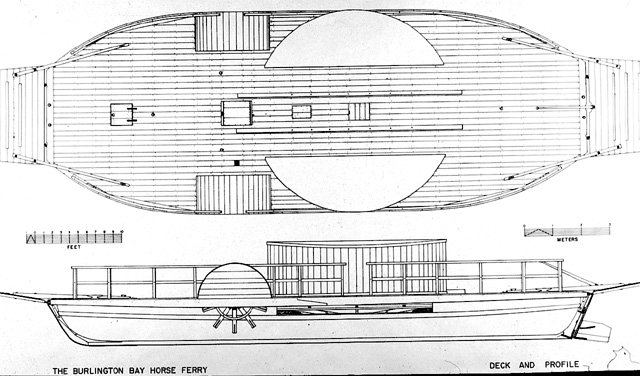

The deck and exterior profile of the Burlington Bay horse ferry. Not the prettiest vessel ever to sail Lake Champlain, but certainly a wonderful example of early nineteenth century technology. The ferry’s hull was 60 feet, 4 inches (18.4 m) in length and 15 feet (4.6 m) in beam, and the deck measured 62 feet, 5 inches (19 m) in length and 23 feet, 8 inches (7.2 m) in breadth.

Ferrying on the lake continues. Throughout our four seasons of archaeological study of the horse ferry wreck its descendants, the Champlain Transportation Company’s ferries Champlain, Adirondack, and Valcour (pictured here) passed nearby on their daily rounds between Burlington, Vermont and Port Kent, New York.

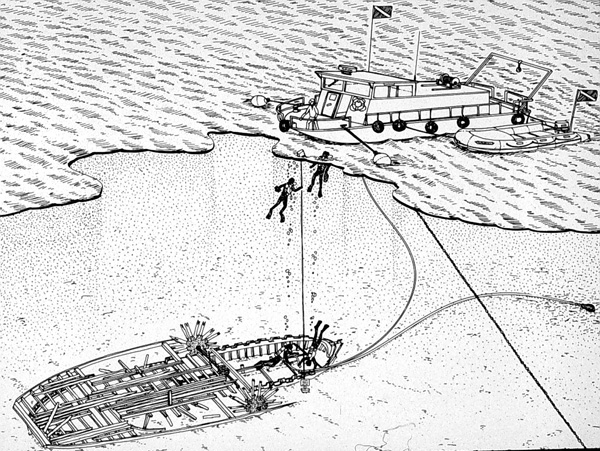

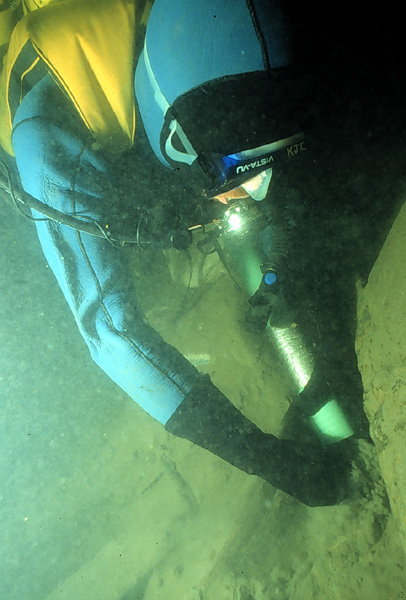

The wreck of the horse ferry was opened as an Vermont State Underwater Historic Preserve in 1989, and in the same year a multi-year program of archaeological recording and excavation was begun under the direction of Kevin Crisman and Arthur Cohn, and sponsored by the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University, the University of Vermont, and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation. The R.V. Neptune, owned and captained by Fred Fayette of Milton, Vermont, served as the project dive vessel.

Want to read more about North America’s age of horseboats and the horse ferry wreck in Lake Champlain? See:

Kevin J. Crisman and Arthur B. Cohn. When Horses Walked on Water: Horse-Powered Ferries in Nineteenth-Century North America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998).