August 11, 2020

Recognizing racism as a public health crisis is just the beginning

Refinery29 cites a 2013 study led by Joe Feagin, Ella C. McFadden Professor and Distinguished Professor in the Department of Sociology, in this in-depth analysis about racism in America.

On Wednesday, August 5, Detroit Governor Gretchen Whitmer officially signed an order declaring racism a public health crisis, reports The Detroit News. The Michigan city joins 19 states, including Texas, Colorado, and California, and a growing number of cities and counties across the U.S. that have also pointed to racism as a determinant of health, according to the American Public Health Association.

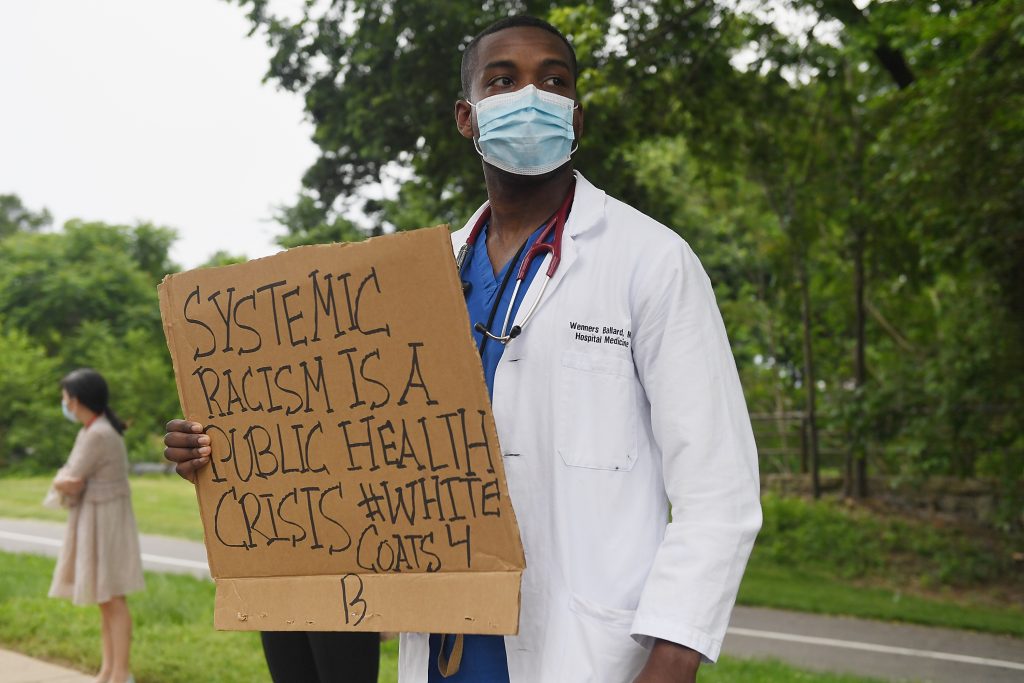

Even employees of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have pushed the agency to declare racism a public health crisis, in a June 30 letter addressed to Robert Redfield, MD, the agency’s director. “At CDC, we have a powerful platform from which to create real change,” the letter, obtained by NPR, reads. “By declaring racism a public health crisis, the agency has an unprecedented opportunity to leverage the power of science to confront this insidious threat that undermines the health and strength of our entire nation.”

That racism affects health is not a point of debate. The current pandemic disproportionately affects and kills Black Americans. Though they account for roughly 13% of the total United States population, Black people make up 23% of COVID-19-related deaths in the United States, according the CDC.

Setting aside coronavirus, medical racism threatens the lives of Black Americans. Black women who see white physicians are less likely to be educated on preventative care, are less likely to be preventatively tested for diseases, and are less likely to be referred to specialty facilities than white females are, according to a 2013 meta-analysis performed by sociological researchers at Texas A&M University.

The recent death of Sha-Asia Washington highlighted the fact that Black people are still more likely than their white peers to die during childbirth. The brutal killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Elijah McClain have drawn increased attention to the fact that Black people are killed by police at over twice the rate of white people, The Washington Post reports. There’s evidence that the burden of living in a deeply racist society has severe affects on mental health, as well.

But while declaring racism a public health crisis seem revolutionary, it’s not a brand-new idea. In fact, Milwaukee County in Wisconsin declared it so in May 2019. What’s more, the action isn’t as big a step toward ending institutionalized racism as it may seem.

“A public health crisis is not technically a legal term,” Paula Tran Inzeo, a director at University of Wisconsin’s Public Health Institute, tells Refinery29. “A crisis has no particular definition. The legal term would be ‘public health emergency.'”

Originally, Wisconsin leaders originally had used the word emergency instead of crisis, says Inzeo. (She’s the director of the Mobilizing Action Toward Community Health Group, which in 2017 identified declaring racism a public health emergency as a priority for Wisconsin.) Some areas, like Minnesota, are still exploring using the label. But there are a few reasons why lawmakers are opting for the term “crisis” instead.

Public health emergencies can only be declared in a few specific situations, including when a disease or disorder presents a PHE, or when an outbreak of infectious disease or a bioterrorist attack exists, reports the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. In some states, governors must get legislative approval to enforce the state of emergency; in others, they can enforce it for a set period of time but need legislative approval to renew it, according to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Getting that approval isn’t always easy. “It’s a political act to call something a public health emergency and it can be challenged. If there isn’t widespread support for it, there can be a lot of legal challenges,” Inzeo says.

Declaring something a public health crisis, however, doesn’t require legislative approval, and there’s no time limit on how long the declaration can apply. There are also no restrictions around who can make the declaration. That may be why we’re seeing so many cities and states doing so.

Of course, the declaration of a public health emergency frees up access to resources, such as government funds or the ability to waive certain laws in an attempt to ease the emergency. Declaring racism a public health crisis does nothing to divert money or legal protections toward the communities who are affected. “There’s no formal regulatory teeth around a crisis,” Inzeo says. “If they are successful at formally declaring a public health emergency, there are some set of guidance or orders.”

But, she notes, “The goal is to allocate resources and things we know will make a difference. Declaring racism a public health emergency is one way to do that — but it’s not the only way,” Inzeo says, adding: “Lots of jurisdictions are beginning to allocate those dollars regardless, so there are a lot of entry points to this kind of work, and it will require shifts in power and shifts in the way we invest dollars at the very root causes of the issues.”

Calling racism a public health crisis does bring awareness to the fact that racism impacts health outcomes, which is a good starting point and hopefully a way to drive action at multiple levels, Inzeo says. Still, the cities and states that sign these orders need to back up their words with concrete, radical actions — or else it’s really just an empty gesture.

Making a public declaration is “an important first step in the movement to advance racial equity and justice,” emphasizes The American Public Health Association. The next steps, they say: the allocation of resources and strategic action.

In the case of Detroit, for instance, the directive Whitmer signed also created the Black Leadership Advisory Council to “elevate Black voices” in the Detroit community and promote legislation that seeks “to remedy structural inequities.” The governor also asked the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to have all state employees undergo implicit bias training for employees. “We must confront systemic racism head on so we can create a more equitable and just Michigan,” said Whitmer (who may be on Joe Biden’s vice president short list, recent rumors suggest) in a statement. “This is not about one party or person. I hope we can continue to work towards building a more inclusive and unbiased state that works for everyone.”

For now, it seems like the city is on the right track. Of course, we’ve seen firsthand that grand gestures toward change don’t always result in enduring action. But a declaration does invite accountability — so now’s the time to contact your congressperson to make your voice be heard in your state. The way our country has been handling the racial injustice pandemic is unacceptable, and it’s time for us to fight for real change.

Originally posted at Refinery29.