February 4, 2021

Historian Who Pushed for the Tubman Twenty is Cheered by its Revival

Elizabeth Cobbs, the Melbern G. Glasscock Chair in American History at Texas A&M University and author of "The Tubman Command," explains why she's excited that the Tubman Twenty is back on track.

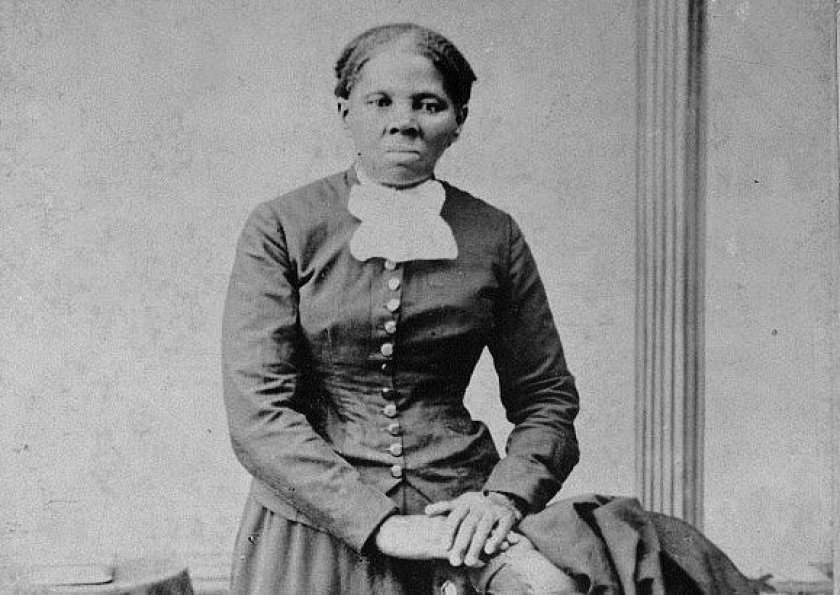

Harriet Tubman, between 1860 and 1875.(Library of Congress)

Harriet Tubman, between 1860 and 1875.(Library of Congress)

By John Wilkens, San Diego Union-Tribune

The Tubman Twenty is back on track. Elizabeth Cobbs, the Melbern G. Glasscock Chair in American History at Texas A&M University, couldn’t be happier.

“This is so long overdue,” Cobbs said as word got out this week that the Biden administration is reviving plans to put 19th century abolitionist Harriet Tubman on the front of a redesigned $20 bill.

Cobbs wasn’t the only one cheered by the news that U.S. paper money will feature a woman for the first time in more than a century, and a Black person for the first time ever. But few are as well-versed in Tubman’s story as Cobbs is.

For her 2019 historical novel, The Tubman Command, Cobbs dove deeply into the Underground Railroad icon’s past, especially her lesser-known exploits as a Union scout and spy during the Civil War.

“She was our first female military hero,” the author said, one later lauded by a Union general for her “remarkable courage, zeal, and fidelity.”

Elizabeth Cobbs(James Shelley)

Cobbs’ research took her to the East Coast, where she visited the area of Tubman’s most daring war-time mission, the 1863 Combahee River raid in South Carolina that freed an estimated 700 slaves. She also went to Auburn, N.Y., where Tubman was buried after spending her later years as a suffragist and a social worker.

“I can’t think of any historical figure who has a record of leadership like hers in so many different areas,” Cobbs said.

Plans to put Tubman on the twenty — replacing Andrew Jackson, the seventh U.S. president — were disclosed in 2016 during the Obama administration, which had announced a year earlier that it would add a woman to the currency lineup as it revamped several bills to make them harder to counterfeit.

“Her incredible story of courage and commitment to equality embodies the ideals of democracy that our nation celebrates,” said Jacob Lew, Treasury secretary at the time. He said the design of the new bill would be unveiled in 2020, in time for the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

The move was widely applauded, especially because it involved the $20 bill, the one most often used for spending. The joy was short-lived, however.

A year later, the Trump administration put the plans on the back burner, citing a need to pay more attention to the security features of the revised currency.

Cobbs watched all this unfold while she split her time between Mount Helix, where she lives, and College Station, Texas, where she was appointed to an endowed chair in history at Texas A&M in 2015.

When she heard about plans for the Tubman bill, her first thought was how great it would be to see a woman featured on a U.S. note. (The last one was Martha Washington, on silver certificates in the late 1800s.)

Her second thought: Is Tubman the right choice?

“I didn’t know very much about her at the time,” Cobbs said. “I think most Americans know as much about her as they could fit on the back of a cocktail napkin.”

When she’s not writing non-fiction books about foreign relations and American history, Cobbs pens historical novels, and she decided to explore doing one with Tubman as a central character.

“I was curious about her,” she said. “It was also not long after Hillary Clinton had lost the presidential election, and it had been interesting to observe her trying to exert a national leadership role. Women don’t have role models for how stern a woman can be, how commanding.”

Tubman turned out to be that role model, Cobbs said.

Elizabeth Cobbs at Harriet Tubman’s gravesite in Auburn, N.Y.

“She talks her way into an audience with the White military leadership of the Union army,” she said. “She has to somehow get people to follow her plans, to not resent her, to trust her judgment. And she does it.”

By the time of the Combahee raid, Tubman had been leading slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad for more than a decade, crossing state lines over and over with a bounty on her head and earning a reverential nickname: Moses.

The more Cobbs learned, the more she came to believe Tubman was the right choice for the $20 bill. But shortly after Donald Trump became president, his Treasury Secretary, Steven Mnuchin, backed away from the redesign.

“People have been on the bills for a long period of time,” he told CNBC in a September 2017 interview. “This is something we’ll consider. Right now, we have a lot more important issues to focus on.”

Trump had made his views known during the 2016 presidential campaign, dismissing the Tubman Twenty as “pure political correctness.” He also praised Jackson’s “history of tremendous success” as a populist. After he was elected, Trump had a portrait of “Old Hickory” placed on a wall in the Oval Office.

As months went by with no sign of progress on the Tubman front, Cobbs said she grew outraged “that no woman was being honored on our currency 100 years after we got the right to vote, and outraged that this specific woman, who was such a hero, was being kept off it.”

She wasn’t the only one upset. A New York designer created a 3-D stamp of Tubman’s face that he and others have used to superimpose her portrait over Jackson’s on the existing $20 bill.

In August 2018, Cobbs co-authored a letter to Mnuchin with Catherine Clinton, a University of Texas (San Antonio) historian, urging the Treasury Secretary to move forward with the new money.

“Harriet Tubman is the very best candidate for this honor,” they wrote. “She is simply the most remarkable and well-known heroine in U.S. history.”

The letter was signed by 125 other American historians. Included were scholars from major universities coast to coast, as well as noted author Doris Kearns Goodwin and documentary filmmaker Ken Burns.

“We never got a reply,” Cobbs said.

On Monday, Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, told reporters the Treasury Department is taking steps to restart the Tubman redesign. She said it’s important for our money to “reflect the history and diversity of our country.”

No details have been released on when the bill might be in circulation. It’s a multi-step process involving several federal agencies — the Federal Reserve, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Secret Service — that begins with design of the new money. What should the portrait be? What belongs on the back side? What anti-counterfeit features will be included? The Treasury secretary has final approval.

Then the Federal Reserve decides how many of the new bills to order, based on a variety of factors, including how many of the old bills are likely to be too torn or tattered to remain in circulation. The bills are printed, issued and then put into circulation. The whole process takes years.

Assuming it finally happens, Cobbs said she hopes some people who see the Tubman Twenty for the first time when it comes out of an ATM will embark on a journey similar to the one Cobbs herself took.

“They’ll see Harriet Tubman and they’ll wonder, why her?” Cobbs said. “And then they’ll learn her story.”

Originally published by the San Diego Union-Tribune.