Incorporating Liberal Arts Into Your Child’s Education

While many things remain uncertain as we start the 2020-2021 school year, incorporating liberal arts into your child’s education remains invaluable.

By Rachel Knight ‘18

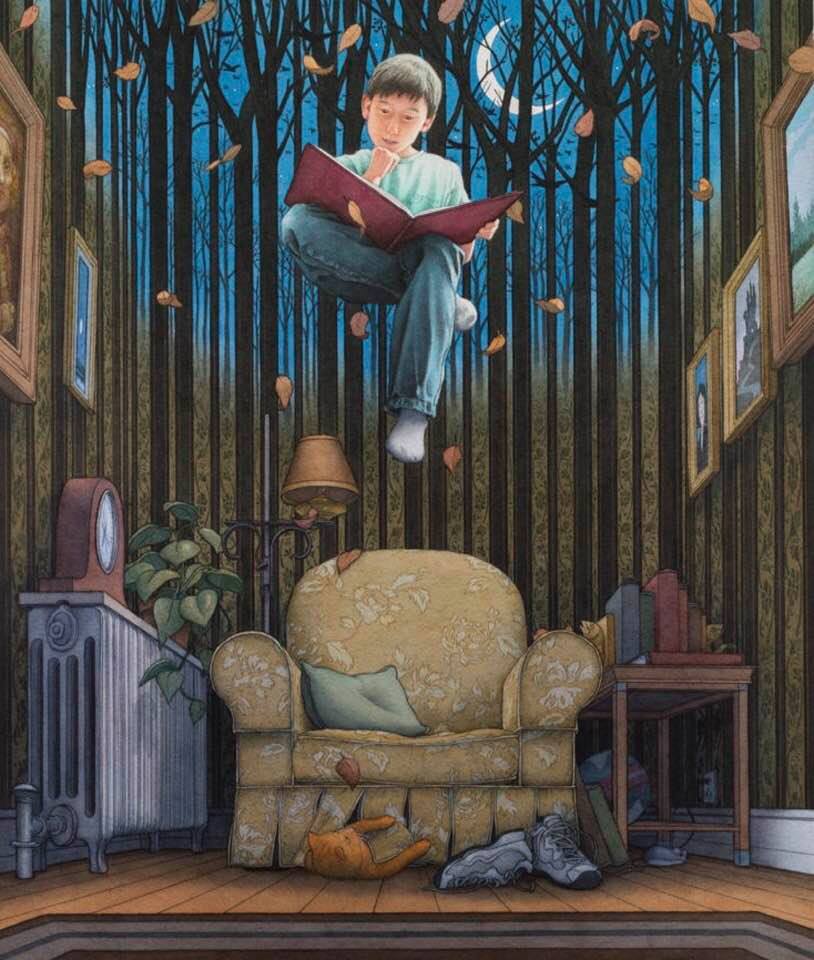

Illustration by David Wiesner that captures the joy of reading as a kid. Dr. Claudia Nelson, English professor emeritus, recommends Wiesner’s picture books for young readers.

Much uncertainty surrounds the 2020-2021 school year, but regardless of where or when children learn, liberal arts remains an essential part of any well-rounded education.

Parents, mentors, and educators can help incorporate liberal arts into children’s curriculum no matter what school looks like this year, according to professors in the College of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M University.

“The liberal arts humanize us,” said Brian Rouleau, associate professor at Texas A&M University whose research traces the importance of youth culture in educating Americans about their nation’s growing global obligations. “They encourage a love of learning, inspire curiosity about the world around us, teach us better judgment, and remind us to maintain a healthy skepticism. These are the values vital to citizenship in a democracy.”

Incorporating liberal arts into your child’s education may be easier than you think. Simply taking the time to share your own history is a great way to spark interest in the past.

“Parents, grandparents, and families more generally should talk to kids about their own histories,” Rouleau explained. “Talk about what life was like for them growing up. Discuss the differences between now and then. Show kids old photos. Show kids old videos. Personalizing the past helps young people connect their own experiences with those of people they know and love.”

Sharing a little of your history is also a good way to bond while encouraging your child to grow and learn. When you share history with a child, you are challenging them to be better than those who came before them, even as the struggles of past people for freedom or justice inspire us to carry on the fight, Rouleau shared.

Like history, literature helps round out your child’s education, according to Claudia Nelson, professor emeritus of English whose book titled Topologies of the Classical World in Children’s Fiction examines works of twentieth- and twenty-first century children’s literature that incorporate character types, settings, and narratives derived from the Greco-Roman past. She said children whose education includes reading literature benefit greatly.

“There are many [benefits], ranging from improving reading skills (as with anything else, practice makes perfect) and establishing a lifelong reading habit to building empathy and understanding of other people, times, and cultures,” Nelson said. “Reading literature is an immersive experience; it involves identifying with characters, caring about what happens to them because these people are real to us while the book has us under its spell, living in the world that the text is describing, and being engrossed by the plot. This is where we start, both as children when we’re beginning to master reading and as adults when we’re first becoming acquainted with a new and engaging work.”

“Little Bear” (a book series recommended Dr. Nelson) illustration by Maurice Bernard Sendak. Dr. Rouleau suggests parents and grandparents share their history with kids to excite them about the past.

In addition to incorporating literary works into your child’s reading list, you can start conversations with them that help develop habits for studying literature.

“Studying literature is slower and more deliberative; it involves thinking about such issues as factors external to the text that have contributed to shaping it, literary style, and repeated patterns within the work that have the effect of creating meaning beyond the level of plot or overt authorial commentary,” Nelson explained. “Meaningful discussion requires both parties to read the book with some degree of attention and enjoyment. Good conversations sometimes start by focusing on some aspect of the book that might have seemed unexpected. ‘You didn’t realize that Dracula is told in scrapbook form. Did you like that?’ Begin with aspects of the reading experience, I’d say, and only gradually move into the studying experience if that seems appropriate to the child’s age and reading skill.”

Whether your child is reading, studying, or both reading and studying literature, their interaction with the text will likely prove invaluable. Similar to how Rouleau described learning about history, reading literature has a way of inspiring young minds to be better.

“The term ‘literature’ connotes quality; we tend to apply it to works whose construction is expert, whose message is profound, whose effect is to teach readers something meaningful about the human condition,” Nelson explained. “Such works deeply repay both reading and studying. It’s always valuable to learn to recognize and appreciate excellence so that we can strive to emulate it in our own lives. And, of course, children’s literature has always been designed to teach young readers values and information that the author, publisher, and surrounding culture deem important. For that reason, children’s literature can often be used across the grade-school curriculum in subjects such as history, geography, science, and even math.”

History and literature are among the liberal arts subjects that traditionally come to mind when thinking about a well rounded grade-school education, but other subjects like philosophy are beneficial to grade-school aged students, too. Claire Katz, professor of philosophy and associate dean of faculties, brought Philosophy for Kids to Texas A&M. She said philosophy can easily be incorporated into a child’s education early in their development.

“Aristotle said that philosophy begins in wonder,” Katz shared. “Children are naturally curious. So adjusted for age, philosophy can be done with very young children. I have colleagues here at Texas A&M and at other institutions who have worked with children as young as 4.”

Engaging with philosophy seems to have endless benefits for kids. It provides them with a vocabulary and means for analysis, which can help them think through difficult and often perplexing questions, according to Katz.

Illustration by Jerry Pinkney, whose books are recommended by Dr. Nelson. This illustration shows that philosophical conversations can start at home (or in this case in the home garden).

“[Philosophy] hones critical thinking and critical reasoning skills, develops the ability to read and listen carefully, and cultivates the ability to consider other perspectives,” Katz said. “Those are the ‘practical’ skills that philosophy develops. But philosophical questions are typically focused on the deeper parts of our lives: friendship, love, meaning, ethics, fairness, truth, etc. These are themes that most people, including young children, think about regularly. Incorporating philosophy in children’s educational environments allows them to explore these questions within the context of what they are learning.”

Katz suggests looking at books and online resources that advise parents and teachers about approaching philosophical discussions with young people. The first she recommends is a website with more than 200 parent-friendly book modules developed by Thomas Wartenberg, emeritus professor at Mt. Holyoke, and his students designed to get dialogue going.

The Philosophy, Learning and Teaching Organization, also known as PLATO, has good philosophy resources for different age groups, Katz said. She also recommends a few books about teaching philosophy for kids —The Philosophical Child by Jana Mohr Lone, Dialogues with Children and Philosophy and the Young Child both by Gareth Matthews, Big Ideas for Little Kids: Teaching Philosophy Through Children’s Literature by Thomas Wartenberg, and Wartenberg’s Big Ideas for Little Kids book series at Rowman and Littlefield. For additional resources, Katz said she’s willing to direct anyone interested to additional online resources.

“Philosophical dialogue can be a lot of fun and it might surprise parents to see the kind of depth and reasoning that their children are capable of doing,” Katz said. “Developing good reasoning and learning to think for oneself are important for anyone to be able to do. But children especially benefit from learning to express oneself, to say what they think and offer good reasons for why they hold that position. By starting early, children develop these habits of mind.”

You can be the champion of liberal arts in your child’s education no matter what school looks like for them this year. Share your history, read together, and start meaningful dialogues that develop philosophical skills.

“Since 1776, American parents have agonized over whether or not their kids are reading ‘the right kind’ of books,” Rouleau explained. “There has always been a fear that if children are raised on the wrong books, they’ll turn out poorly. History, however, tends to suggest that most of those worries are misplaced. It’s better that kids read something, anything, rather than be discouraged by overprotective parents. The liberal arts are essential to any well-rounded education.”