Why Some COVID-19 Vaccine Communications Fail And Others Succeed

Professors from the College of Liberal Arts explain the successes and failures of COVID-19 and vaccine communication to the public.

By Mia Mercer ‘23

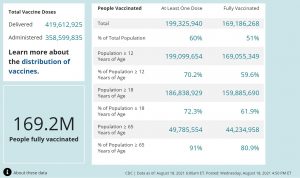

Despite efforts from government and health care agencies to spread information about COVID-19 and the vaccine, this graphic from the CDC shows only half of the population has received their vaccines. Faculty from the College of Liberal Arts explains that this could be due to the constant circulation of misinformation on social media.

Experts agree that just because we can get any information online doesn’t mean we should blindly trust it. In order to prevent more casualties and protect communities, public health and government agencies are working to communicate COVID-19 and vaccine information to the public. Despite their best efforts, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that only 51 percent of the United States population is fully vaccinated. Faculty from the College of Liberal Arts reveal some of the pitfalls of health and crisis communication during the pandemic caused by a lack of crisis preparation and the constant misinformation on social media.

“Communication with the public about COVID-19 and vaccine information is important because that’s the best way to prevent the spread of the virus and allow society to operate normally,” organizational communication professor Timothy Coombs from the Department of Communication said. “But from the very start of the pandemic, we didn’t have consistent messaging. The federal government sort of took a hands-off approach and left it to the states, the cities, and even corporations. And that’s been a problem because one of the basic principles any crisis manager learns is that the message has to be consistent to be effective.”

Often called the “father of crisis communication,” Coombs developed the situational crisis communication theory. In order to help organizations effectively respond to a crisis, this theory looks at key factors within a situation — like the type of crisis it is, if there is a history of crisis, and how responsible for a crisis people will consider an organization to be. According to Coombs, the more responsible an organization is, the more they should focus on victims and others within the crisis.

“It’s good to apply this theory to the current pandemic and vaccine situation, because for health crises, the focus is on the victims and that’s what it needs to be on,” Coombs explained. “For instance, corporations need to talk a lot about what they are doing to protect customers and protect employees. And all the government entities need to think, ‘How can we best reach everybody?’ And that’s a real dilemma for organizations and for these public health officials.”

Although public health agencies are working to reach everyone regardless of their ability to access the internet, social media remains a huge factor in how most people receive information. According to health communication professor Lu Tang from the Department of Communication, this is a problem because social media is better at spreading false information than facts.

In today’s society, almost everyone utilizes social media, making it a vital source of communication. However, because false information often looks more interesting, misinformation about the COVID-19 and the vaccine is spreading at a faster rate than facts.

“When we studied vaccine misinformation on Twitter, researchers found tweets containing vaccine misinformation are more than twice as likely to be retweeted than tweets containing correct information,” Tang shared. “This is because misinformation is usually sensational and looks interesting, while tweets containing correct information sound mainstream and non-interesting.”

According to Tang, vaccine misinformation has been circulating online since the start of the internet and is more accessible to the public today than it was in the early 2000s. This is partially due to the fact that social media allows people to find like-minded individuals and mobilize and advocate for their shared beliefs. Although we’re not able to completely prevent the spreading of false information about COVID-19 and the vaccine on social media, Tang said using social media to inform the public about a crisis and its solution has benefits.

“Social media is a big part of our society these days and we need to try and understand the mechanism of social media more so we can respond accordingly,” Tang said. “We are not helpless. If we can find out enough about social media and their roles in promoting misinformation, fact, or combating misinformation, then things can be done, either by appealing to the corporate responsibility of those big companies, through legislation, or through public opinion.”

Tang also said some social media companies are becoming more aware of the issues their platforms help create in spreading false information to the masses, and some are even taking steps to combat the spread of misinformation about health and vaccines.

According to both Coombs and Tang, social media should be depoliticized in order to effectively combat COVID-19 and vaccine misinformation. They also said there needs to be empathy involved when communicating with the public.

“The messages we get from many government entities are that they are thinking more about themselves and elections than they are thinking about public health and public safety,” Coombs stated. “If you look at the messages coming out from local communities, they’re very good because they’re focused on the communities, but when you start looking at the state and the national level, we get a lot of messages that are political as opposed to public health, which doesn’t help. This is a time when people do need to be united and think about what’s best for public health.”

As the pandemic continues, communicators continue their endeavors to get the right messages out and to stop the spread of false information.

“One of the key lessons we need to take away from the COVID-19 experience is that we need to prepare ahead of time,” Coombs said. “You have time prior to a crisis to think, ‘Who are my audiences, who are likely to resist.’ You can respond more quickly that way. If I make those decisions after a crisis, I’ve lost time. If I make those decisions before a crisis, I save time. And in this case, time is lives, hundreds of thousands of lives within the United States.”