Who discovered the Americas?

Many people believe that Christopher Columbus discovered the New World; however, they forget about the Native people who lived here before his arrival — these are the real first explorers. The Center of the Study of the First Americans helps fix this conception and asks new questions.

By Hannah LeGare ’19

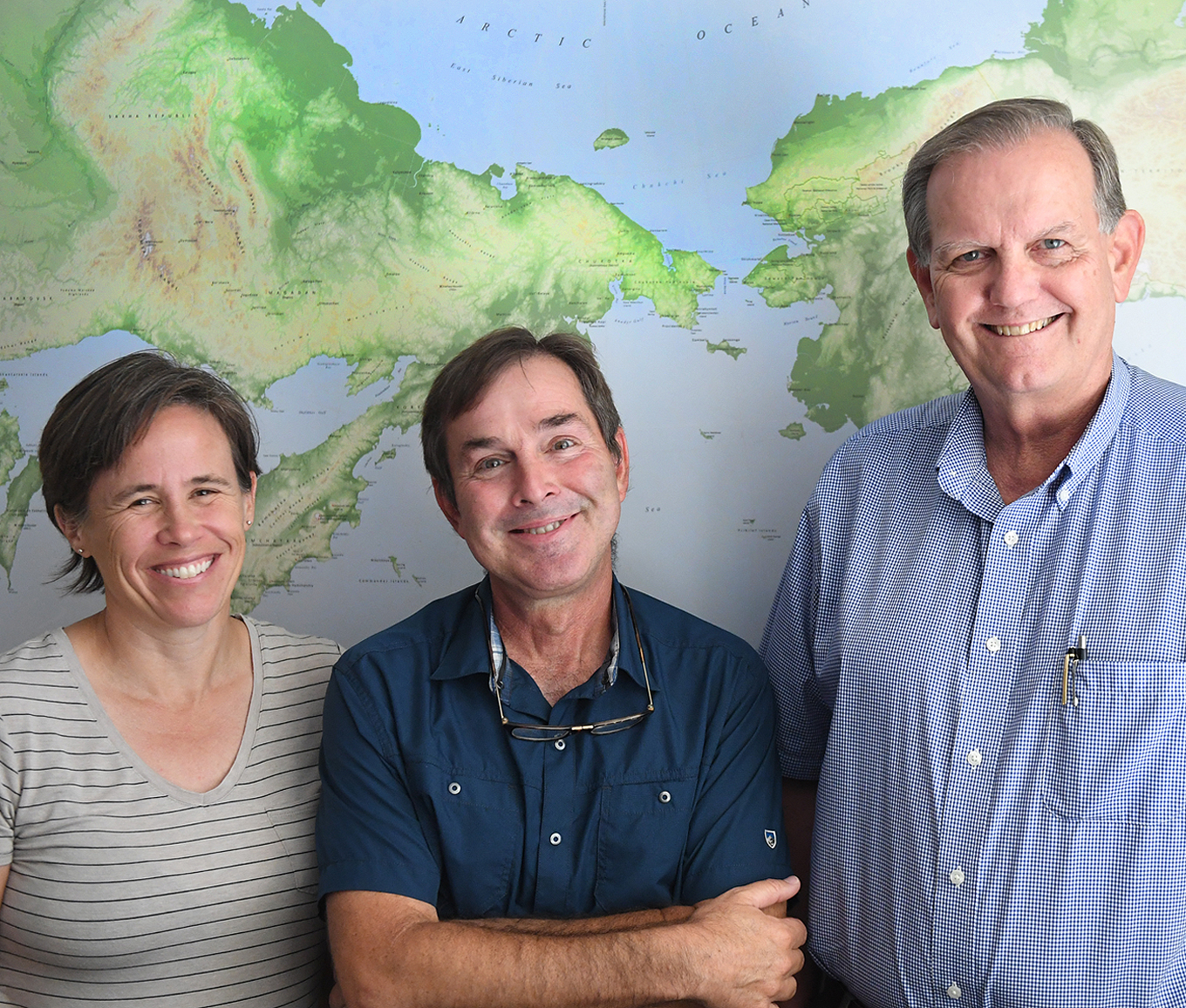

From left to right: Kelly Graf, Ted Goebel and Michael Waters of the Center for the Study of the First Americans, stand in front of a map showing where modern man crossed over from present day Siberia to North American while standing in their offices at The Anthropology Building on the A&M campus. Photo: provided.

Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples’ Day? The holiday can arouse a sense of confusion — what should we call this day?

Both of these days signify something different. Columbus Day heralds Christopher Columbus and his crew’s arrival to the New World, initiating the Columbian Exchange which introduced the transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, and technology between the New and Old Worlds. Columbus’s arrival also signaled the decline of Native populations through genocide and oppression. Indigenous Peoples’ Day reimagines Columbus Day and uses the day to raise awareness about the true original settlers of the Americas and their histories.

Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognizes that Native people were the first inhabitants of the Americas, including the lands that later became the United States of America. For the Center of the Study of the First Americans (CSFA), this isn’t just a holiday, it is every day. The mission of the CSFA is to pursue research, train students, promote scientific dialogue, and stimulate public interest in the first people that settled the Americas at the end of the last Ice Age. The Americas were not discovered by European explorers such as Columbus, but by people hailing from Asia nearly 16,000 years ago. All Indigenous Americans are derived from these first peoples.

Michael Waters, director of the CSFA, is one of several leading experts at Texas A&M focused on understanding these first peoples. Their work seeks to uncover the past through archaeology and research.

Who were these first peoples?

Waters, along with his colleagues Ted Goebel and Kelly Graf, study the first peoples that came to America during the end of the last Ice Age (or Pleistocene). According to Waters, about 24,000 years ago, these people headed towards Beringia, a large land bridge between modern-day Russia and Alaska. These peoples, an ancestral mix of mostly ancestral Asian and ancient Siberian populations, would branch out into different areas of North America. Around 16,000 to 15,000 years ago, the groups that traveled south of the ice sheets would branch out again to create the main group that populated the Americas.

Genetic work, specifically the analysis of mitochondrial DNA and genomes of prehistoric individuals, helped the CSFA discover more information about these earliest peoples. However, most of the information about these people has come from archaeological excavations conducted by the CSFA in North and South America.

For Waters, an archaeological perspective is needed to learn about these peoples of the past. Historical documents only go back to the time of Columbus and after, but archaeological digs are the only way to learn about the first Indigenous explorers and settlers.

By digging archaeological sites, carefully recording of the geological layers, and plotting of artifact locations, archaeologists and students of CSFA piece together the story of the lives of these early hunter-gatherers. Their main food supply came from hunting native animals and gathering local plant species. Over time these hunter-gatherer groups would grow in population and expand from North to South America.

Descendants of the first peoples

“It is mind-boggling to think about how the first people to enter the Americas explored a continent filled with strange animals and different environments, and how they successfully settled these varies places and give rise to the Native groups that the European colonizers interacted with,” said Waters.

It is important to recognize that there were people who lived in the Americas long before Columbus or any Old World explorers colonized it. These Indigenous people were the original settlers of this strange and foreign land. They created thriving communities and networks of trade. They hunted, gathered, and foraged for food. They developed agriculture and manned great empires. The arrival of conquistadors would adversely affect these tribes through atrocities such as forced labor and disease epidemics. These once large nations, who were descended from the original peoples for thousands of years, would be destroyed in hundreds of years.

As the CSFA discovers more about the first peoples of America, they reflect on why it is important to acknowledge these Indigenous peoples.

“We must always remember that we are investigating the ancestors of contemporary Indigenous peoples and as such, we should strive to include Indigenous Americans in our studies as partners in our quest to uncover their past,” said Waters in a recent paper. Waters recognizes that collaboration between scientists and Indigenous peoples will enrich our understanding of the story of the first Americans.

The Department of Anthropology’s work helps illuminate the past.

“The archaeological record is like a book with words that are scrambled and pages have been ripped out or put in different spots,” said Waters. “We get the chance to put the book back together.”

Waters, the Department of Anthropology, and the Center for the Studies of the First Americans will continue to piece the pages back together, one book at a time. Especially in regards to the question – who discovered the Americas first: clearly Indigenous peoples.