Beyond and before “Boo”: A Halloween story

Halloween exists beyond symbols of “Boo!” and scary movies. Two professors in the College of Liberal Arts trace Halloween’s historical and cultural beginnings and explain the concept of “liminal spaces” in our world and that of the ancients.

By Hannah LeGare ’19

When we think of Halloween, we don’t immediately think of the term “liminal spaces.” We think about spooky vibes and the sugar-induced coma we might experience after eating one too many Snickers bar. A liminal space is the gap between the holy and secular, and this is exactly what marked the origins of Halloween.

Two professors in the College of Liberal Arts help us think beyond “Boo!” and candy corn. Their areas of research — from the history department to the religious studies program — show the relationship between Halloween and liminal spaces, and how it evolved to the commercialized holiday we know today.

Not so spooky origins

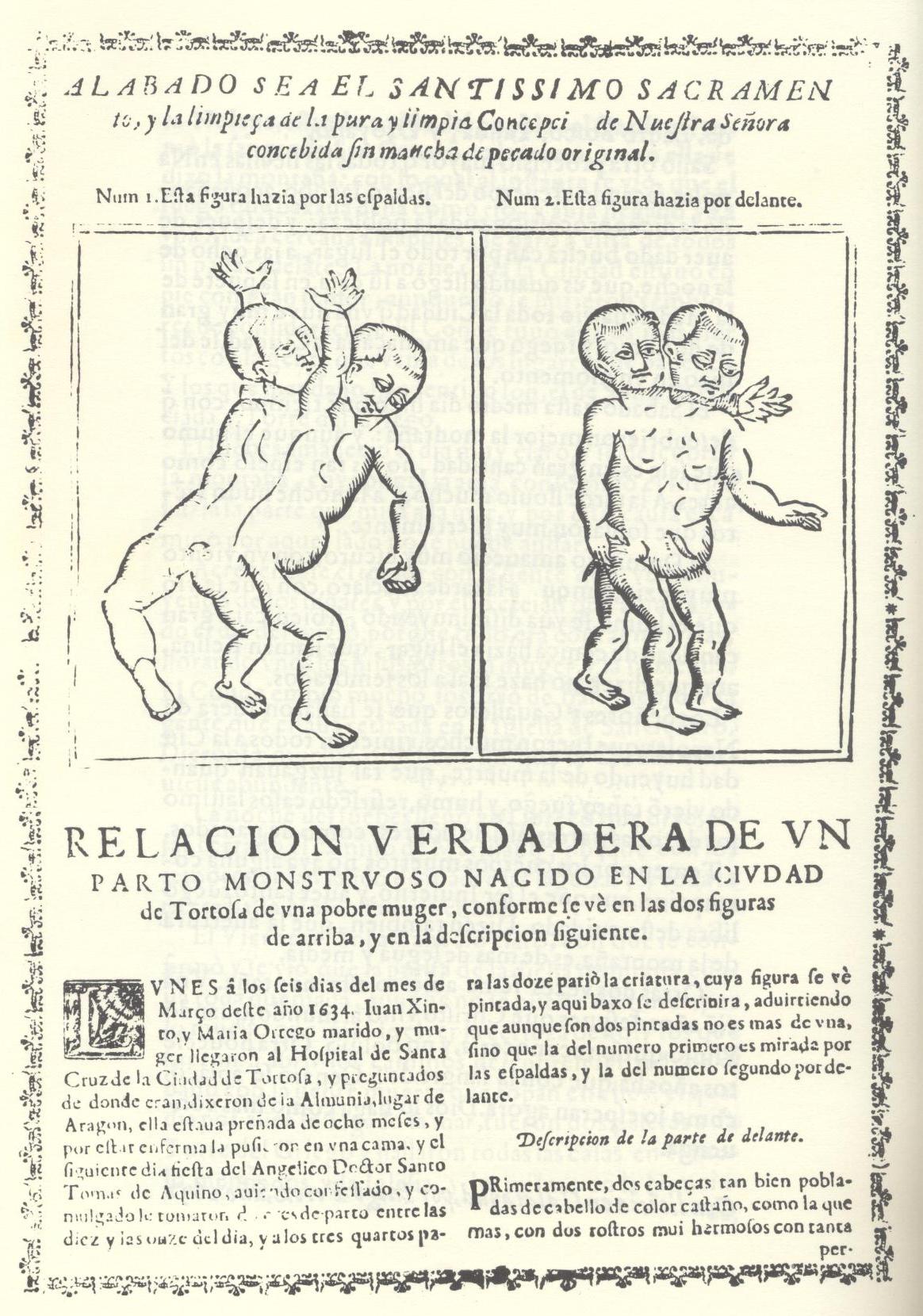

17th-century tabloid about a “monstrous birth” of conjoined twins. This is an example of tabloids that were written about inexplicable moments in life. Photo provided by Hilaire Kallendorf.

Daniel Schwartz, associate professor in the Department of History, studies the intersection of the Late Roman Empire and Christianity and the Christianization of Roman territories in late antiquity. He calls us to remember when Halloween occurs in the year. It’s during a time of significant changes to the weather and the turn of the seasons — in essence, it’s the time of the harvest. In agrarian societies, there were festivals and days devoted to celebrating the coming of the harvest.

“There was very little that did not touch the religious in this time,” said Schwartz. These agrarian communities believed the gods were responsible for healthy crops, disease, and rain. It was important for these people to honor the gods in both prosperity and poverty, which includes honoring the gods through harvest festivals.

While harvest festivals were generally universal across most people groups, Halloween’s traditions have strong ties to a specific agrarian society — the pre-Christian Celts. These people sought to connect to the supernatural or divine beings that they believed affected their everyday lives.

“The pre-Christian Celts did all of these religious rites: they lit bonfires, they had raucous parties, they sacrificed animals, and they ate grain from the harvest,” said Schwartz.

The Celtic harvest festivals, arguably the early predecessors of Halloween, tie together a reverence for divine beings and unholy behavior.

Schwartz’s recognition of the supernatural in Halloween’s beginnings is similar to Hilaire Kallendorf’s understanding.

Hilaire Kallendorf, a professor of Hispanic and Religious Studies, researches the many aspects of religious experience, especially related to literature and culture. One of her classes delves deep into Hispanic religions, where students learn about monsters, evil omens, and exorcisms (to name a few topics).

Kallendorf’s grasp of Halloween relates to Hispanic traditions and cultural elements. Specifically, there are supernatural elements and beliefs in Hispanic culture that attempt to explain the unexplainable.

One example of the unexplainable includes “monsters”. According to Kallendorf, the word monster comes from a Latin verb “monstrare” which means “to show.” In old Spanish tabloids from the 17th-century, there were depictions of deformed babies that were viewed to be from “monstrous births.” While modern readers may be distressed at the tabloid, 17th-century readers thought these babies were a sign from God showing the parents’ sin.

The word ‘monster’ was loaded with cultural connotations. Then and now, people make relationships between the sacred (God) and the secular (the sign).

Liminal spaces

According to Schwartz, just about everything gets connected to belief in the supernatural — even the word “Halloween.”

Halloween means “hallowed evening,” or more specifically, All Hallows’ Eve. All Hallows’ Eve (Oct. 31) preceded the holy days of All Saints’ Day (Nov. 1) and All Souls’ Day (Nov. 2). These days pay homage to Christian martyrs or saints, or God’s holy people, who have passed away and are in heaven.

For Hispanic or Latinx people, Halloween is also the day before Día de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead), a time of honoring and welcoming the souls of departed loved ones.

“My Mexican students are surprised that Day of the Dead is a fusion of Aztec and Spanish cultures,” said Kallendorf. She surmises that sugar skulls, a classic symbol of ofrendas (offerings), are Aztec due to evidence of human sacrifice found in Aztec ruins. Similar skeletal decor can be found in modern Halloween practices today.

The mixture of Aztec, Mexican, and Spanish cultures blends with Catholicism and Christianity in Latinx countries and regions. Like the pre-Christian Celts with early Halloween practices, the Day of the Dead shows the phenomenon of combining devotion to the divine with more seemingly unholy elements (like skulls on ofrendas).

Thus, when you combine the pre-Christian practices dealing with the supernatural, harvest festivals connecting to All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, and days honoring the dead with offerings, there is the concept of liminal spaces.

“Liminal spaces are the gaps between the sacred and the profane,” Schwartz said.

For example, it’s like when people carve pumpkins. People carved pumpkins (or sometimes turnips), lighting them with embers, in order to ward off evil spirits. The act of carving a pumpkin is a liminal space because it relates the earthly pumpkin with the otherworldly spirits. For Kallendorf, another liminal space is shown when someone visits the grave of a loved one on the Day of the Dead and lays out food and gifts for them. This resembles a shrinking of the gap between the here and the beyond.

Liminal spaces are diminished during the holidays that merge the sacred and the profane — like Halloween.

Tricks aren’t always treats

Trick-or-treating wasn’t always asking for candy and dressing up in costumes, either. In centuries past, it was poor people going to lords’ houses and asking for food, drink, and money. Schwartz explained trick-or-treating as a type of giving alms; but while almsgiving, there could be a potential threat from the poor to vandalize the property of a stingy lord, thus the notion of trick or treat.

Similarly, Kallendorf and Schwartz agree that during these moments of connecting the secular and divine, people believed hierarchies of society could be disrupted. Therefore some sought to overturn social conventions or believed they could get away with petty crime. This is where the vague history of pranksterism on Halloween originates, as well as where fear and anxiety entered the holiday.

“As a society, each time there is a moment of crisis in liminal moments we project our anxieties onto them,” said Kallendorf.

In the 17th-century, for example, when people examined one of the aforementioned “monstrous births,” they believed it was a warning that something, especially something momentous or calamitous, was likely to happen. It became a tangible representation of their intangible fear.

These cultural crises affect the way we view Halloween. It is a sacred and secular holiday, a day in which anything can happen.

More than just “Boo!”

Today, Halloween has been mass commercialized, which is why we think of candy, costumes, and scary movies — not liminal moments.

According to Schwartz, religious and traditional Halloween stories and customs were brought over by European immigrants in the 19th-century. For example, the United States adopted several customs, like almsgiving, which turned to a cultural creation of trick-or-treating. The customs were brought back to Europe with less of a religious designation, instead demonstrating an American flair and the dollar sign.

Now people all across the world dress in costumes, throw lavish Halloween parties, and spend inordinate amounts of money on pumpkins. Yet a remembrance of the holiday’s past and history is helpful to chart how it impacts us today.

Halloween goes beyond “Boo!” and reminds us of liminal spaces and the ever-changing culture we live in. The gap between the sacred and the unholy, Kallendorf said, shows that not everything can be explained by reason — there are still elements that require faith.

“If we ignore the realm of the mysterious, we are denying a big part of who we are as human beings.”

Want to learn more from our knowledgeable College of Liberal Arts professors? Consider taking History of Christianity, Reformation to Present (HIST/RELS 222) or Hispanic Religions (HISP/RELS 471) to dive deeper into the world of the sacred and secular.