Libro Albedrío: A Step Forward in Spanish Writing

Hispanic Studies professor Eduardo Espina shares the story behind his most recent book “Libro Albedrío” and what its success means to him.

By Mia Mercer ‘23

Espina’s latest book, Libro Albedrío, is a compilation of essays focusing on contemporary issues and is what many critics are calling his latest original masterpiece.

When Hispanic Studies professor Eduardo Espina was 15 years old, he read a line from T.S. Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock that changed his life forever; “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.” Although just a few words, Espina said reading that line made him forget all his troubles. From that moment on, he dedicated his life to writing, using the feeling he got from reading T.S. Eliot’s words as inspiration to write with his mind and the imagination in a complete state of freedom. Now, Espina is a successful writer and poet living in College Station who has published dozens of academic articles, around 40 book introductions, notes and reviews, and a dozen books of poetry and essays including what many critics consider his latest original masterpiece, Libro Albedrío.

Published this year in Madrid and Mexico City, Libro Albedrío is a book composed of several essays about contemporary issues from the way we live to the idea of creation. Since its publication, Espina’s book has received several praiseworthy reviews including one by Argentinian critic Quintín that called Espina’s essays “the best writing in Spanish north of the River Plate and south of the Rio Grande.” The book was also featured at the Feria del Libro in Madrid, Spain, one of the most important book fairs in the world.

“In some way, I wrote this book to go against the grain of what is written today,” Espina shared. “I talk about relevant issues like the loss of originality and innovation in creative writing and thinking, lack of attention during the acts of writing and reading, and also the way we see things, among other topics. For example, one issue I wrote about in the book is about the gaze and our distracted relationship with visual reality. Our gaze is influenced by the reality we live in. So when we see the many things that dire in society we must consider in what way those issues affect our perception of beauty, which does not perish and continues generating interpretations. We must recreate the idea of beauty through the eyes of a perception that gives greater percentage of importance to what I would call ‘original genius’.”

Before Espina discovered his love for reading and writing, he was an avid soccer player in love with the girl next door. When he finally worked up the nerve to invite her to his soccer game, she abruptly turned him down.

“She told me in one second ‘I hate soccer.’ And, like an idiot, I asked ‘so what do you like?’ ‘Poetry,’ she told me and then invited me inside her house,” Espina shared. “I asked her – her name was Patricia – what poetry she liked and she said Pablo Neruda and she leant me two books by him; Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair and Residence on Earth. Can you imagine it? I had just turned 14 years old. I went home, I started to read carefully, without stopping, and I found that memorable verse: ‘Es tan corto el amor, y es tan largo el olvido’ (‘Love is so short, forgetting is so long’), which blew my mind. I realized I didn’t want to be a great soccer player like Pelé – I wanted to be a poet like Neruda. Many decades after that day, I’m still trying. Apollinaire said that ‘poets have no age.’ Therefore, I plan to continue, as if nothing.”

After his introduction to the world of poetry, Espina immediately began his writing journey, and entered a high school poetry contest where he took home the gold with his first love poem.

“I thought the poem was not good, but I sent it anyway and won,” Espina recalled. “I received the comment that my poem was full of very good imagery and I realized that God was talking to me and showed me my destiny was to be a writer and a teacher, because the people I most admired, besides my parents, were my teachers, who motivated me to be a writer and suggested which books I should read. Since then I get up every morning and I’m the happiest person on the planet, especially when I go to teach, after having spent two hours in the morning reading and writing. If I die tomorrow I can say I had the best life imaginable and it started at 15, when I read and wrote poetry for the first time.”

Espina said each of his books takes years to complete, with Libro Albedrío taking five years and 20 rewrites before it was ready to publish.

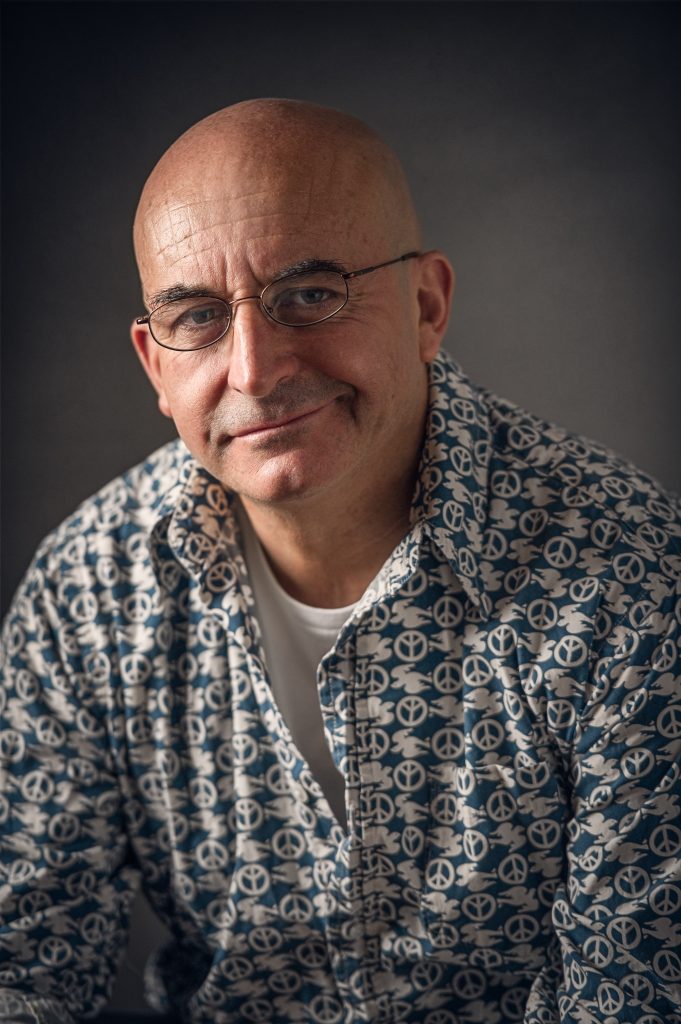

Espina said he is the happiest man in the world because he gets to do the three things he loves most: read, write, and teach students, including Alex Garza who captured this photo of Espina.

“This book was a labor of great craftsmanship because each sentence had to create this feeling where you say ‘this sentence blew my mind’ and you stop,” Espina explained. “People have the feeling that writers enjoy writing, but this is wrong. Nobody enjoys writing. Students complain that ‘oh I have to write eight pages for your class’ and I would complain also. Writing is like dancing. You go to a wedding and maybe you don’t want to dance because you are tired. Then the bride invites you to dance and suddenly you want to dance all night. Writing is the same. You activate it when you have inspiration and imagination. And this book, Libro Albedrío, gave me the free will to realize this is my moment. I’m living this life dancing (although neither polkas nor waltz).”

Espina said the biggest challenge in writing Libro Albedrío was the corrosion associated with the passing of time, which wears everything down.

“You hear a song from the 90s and you say ‘wow this song is outdated’ and that’s a similar concern for the writer,” Espina shared. “How can you write in a way where 20 years from now, it’s going to still be original? So that’s the point of my book. Readers are tired of reading about political, historical, ethical and social issues. We need to instead give them something else to think about starting with language.”

As readers pick up Libro Albedrio, Espina said he hopes they see his book as a dialogue with them.

“Everybody wants to be a best-seller. But I just want to be a great seller. A great seller in terms of great readers,” Espina said. “My book is proposing that the readers listen because these are problems that concern you and me. It’s like saying ‘I am older than you, and I have this experience as a reader and as a writer, what do you think about my opinion?’ And since this is a book going in several directions, I expect a dialogue. It’s not like academic books where if you have a name, the feedback most of the time is going to be great because other professors in the academic circle can read it and people won’t attack you because they know you can attack them back. Nevertheless, when you go to the real world of readers and critics, anybody can receive and review your book, who doesn’t know who you are, and they can destroy you. This is great about creative writing, the fact that when you write, you don’t know who your reader is going to be. For example, suddenly I realize with this book I am connecting with a new generation of readers, which adds years to my life, therefore, thanks muchachos.”

Not only is Espina proud of his work, he is also blown away by the feedback he’s received.

“In my opinion, Quintín is the best literary critic and book reviewer of Argentina,” Espina explained. “When he praised my essays, it was the best compliment I could receive. To have good reviews in Madrid, Mexico City, in Buenos Aires, this is what every writer in Spanish aspires to have – to have the best critic talking about you. To sell or not to sell books, I cannot control that, but good writing is my responsibility. And I believe I did it.”

Having fallen completely in love with his craft, Espina is living the life he always dreamed of having here in College Station. In fact, he says he is thankful to Texas A&M University for giving him the time to do the two things he loves most; writing and teaching.

“I’ve been here for 36 years, and I don’t know if I could do this work in a different place,” Espina shared. “I love Texas, the state and the people, and that’s why I feel I can communicate with the students well because I love to teach here. I’m also obsessed with writing. If I don’t write I feel like I’m dying – like I’m wasting my time. Texas A&M gives me the free time to write, and produce books and articles.”

Since the publication of Libro Albedrío, Espina has taken no breaks in his writing. Currently, he is working on several projects including a memoir about his life living in the U.S. called One Ego Ago, an academic book about the craft in original writing called Poetics of the XXI Century, and two new books of poetry on the subject of time and death. He is also completing the creative-academic project for which he won the Guggenheim Fellowship.

While he continues to put his pen to paper, Espina said he is creating new ways of writing and is eager to share his work, especially with those interested in the news of the imagination and in sentences that want to save themselves from the wear and tear of time.

“In some ways my writing is trying to create a piece of abstract thinking and encapsulate it in many good sentences that at the same time represent the moment in history in which I live. It would be horrible to leave this life without having done something in the discipline which I have been working for so long,” Espina said. “The best comment I received about that was from a Mexican writer that I admire very much, who said with [Libro Albedrío] the Spanish language took a step ahead. In many aspects this book gave me a second life and I think reading it will also inspire people to write about realities that have to do with the imagination and with feeling more alive in the company of words.”