Are We Living In James Madison’s Nightmare?

Professors in the Department of Political Science address how our current government and society compare to the America James Madison feared.

By Tiarra Drisker ‘25

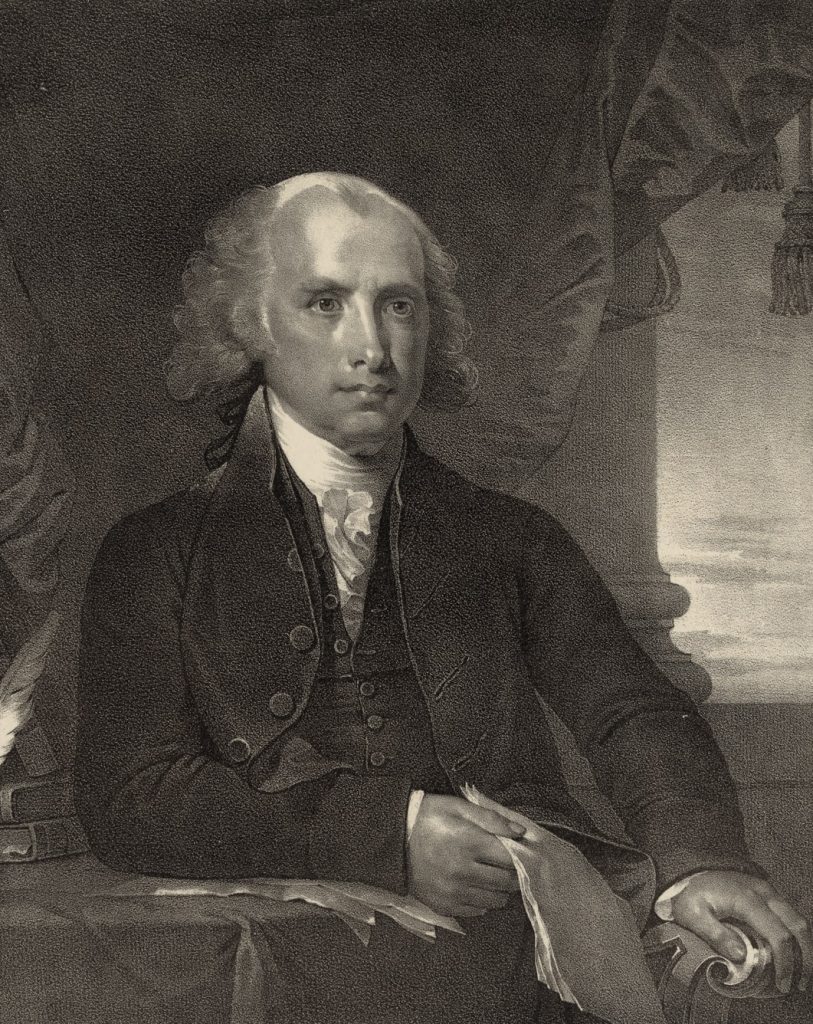

James Madison, a Founding Father also known as “The Father of the Constitution” and the fourth president of the United States, had a very detailed image of what a failed America would look like. Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, wrote extensively in The Federalist Papers to warn a budding new democracy of the dangers of mob, or faction, rule.

When pondering about the possible contents of the Constitution, Madison was adamant about avoiding the mistakes other governments and societies made throughout history. He was so adamant that he read countless numbers of books on the history of these failed democracies. After hours upon hours of research, Madison came to a conclusion: direct democracy led to mob rule and political faction. According to Pew Research Center, now Democrats and Republicans are more ideologically divided than in the past and more democrats and republicans think the other party has policies that threaten the nation. Does this polarization reflect Madison’s nightmare?

“The ‘polarization’ that we are seeing today, while perhaps worrisome, is nonetheless a normal and continuing feature of American politics,” James Rogers, a professor in the Department of Political Science, said. “Indeed, while the political polarization we see today might be greater than existed during the 1950s in America, the evidence suggests that America today is perhaps less polarized than in the 1850s or 1920s. This is not to minimize the polarization that exists, but to recognize that polarization is not a novel feature of American politics. It is something that has always existed since the very start of the Constitution, with the bitter divide between Jefferson and Hamilton over the nature and power of the U.S. national government.”

The faction that Madison refers to actually has little to do with the individual parties and instead focuses on groups holding different beliefs on what advances the public good. To prevent the rise of factions and mobs, Madison supported the separation of powers that is evident in our government today, however, the laws in place to maintain that separation of powers may be being abused. For example, Republicans have not won a majority of the presidential vote since 2004 and they can control the Senate by winning small states but never commanding a majority.

“Madison designed a constitutional structure that would frustrate majorities,” Kirby Goidel, a professor in the Department of Political Science, said. “His reasoning was simple: democracies first gave way to demagogues then to mob rule and finally to tyranny. The contemporary climate turns Madison on his head. The checks and balances Madison put into place to protect against democratic majorities are being abused by political minorities. The Supreme Court is perhaps the most obvious example, though keep in mind that Republicans worked for 50 years to secure a conservative majority on the court by winning elections and timing retirements to assure conservative justices were replaced by Republican presidents. ”

While Madison’s structure is somewhat successful at preventing mob rule or demagogues, it still has its loopholes and makes it difficult for congress to tackle large issues.

“The rules allow either party to frustrate political majorities and assure nothing much gets done,” Goidel explained. “Our congress isn’t very productive. Long-term problems such as deficits and climate change go largely unaddressed, and we are failing to make adequate investments into research, education, and infrastructure: the type of investments that can yield long term benefits and a brighter future.”

Whether or not we are living within Madison’s nightmare is subjective, but there are things we can learn from his warnings and implement into our current government and society.

“Going forward, we are going to have to seriously rethink the Madisonian design,” Goidel shared. “Other political systems, based on proportional representation and with parliamentary systems, appear to be functioning more effectively. Our system encourages politicians to take visible stands while playing to their base constituencies, but doesn’t reward them for actually solving problems. “