Building a Better World With Black History

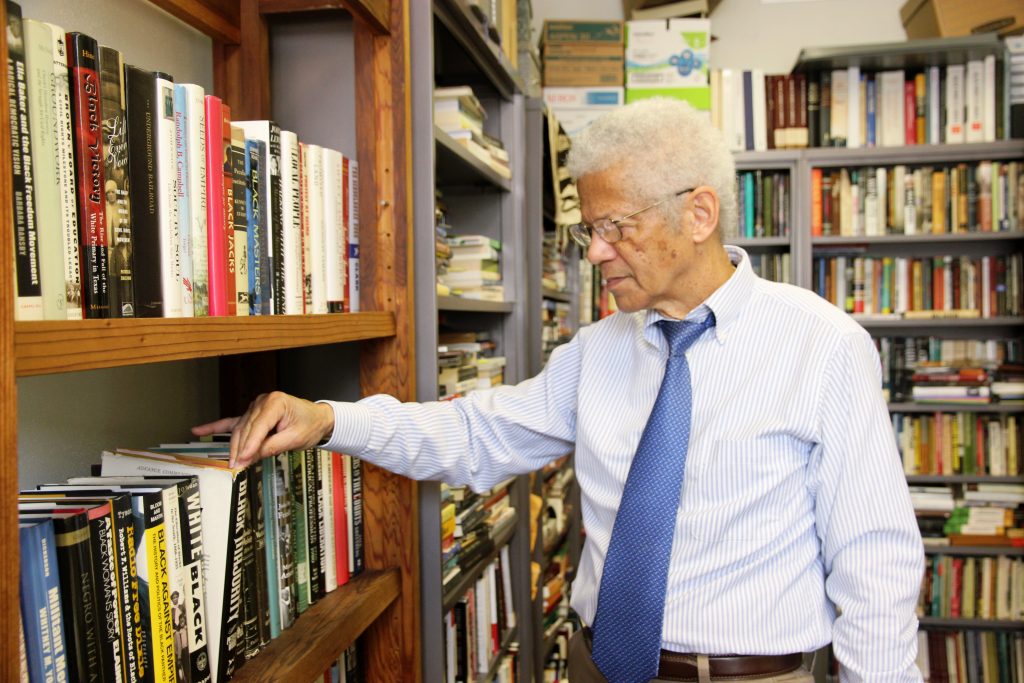

Albert Broussard, once a poor Black kid in San Francisco, now teaches what he wishes he had been taught: Black history.

By Tiarra Drisker ‘25

Photos by Anna Burson ’24

Even as a child growing up in a poor, single-parent household in San Francisco, Albert Broussard was curious about Black history. He had a total of two Black teachers and the only time he was taught about Black history was during Negro History Week, a week-long celebration of Black history founded by Carter G. Woodson that eventually became Black History Month. Eager to discover more about his ancestors, Broussard searched public libraries and scoured his house for any information he could find on the topic. During his quest for knowledge, Broussard found a passion within himself: he wanted others to know about Black history as well. This sparked his devotion to teaching everyone about not only the struggles of Black people in America, but the history of people of African ancestry around the world.

Broussard received a full scholarship to Stanford University for his undergraduate degree and pursued teaching in his graduate years. He became the first Black professor within the College of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M University to be promoted from associate professor to full-time professor. Along with these accomplishments, Broussard has published textbooks and is on the Board of Directors for the largest online Black history website in the world, blackpast.org. The accomplishment he is most proud of though is creating the first Black history course at Texas A&M.

Before Broussard became a pioneer within Texas A&M, he was just a curious Black kid in San Francisco.

During his quest for knowledge, Broussard found a passion within himself: he wanted others to know about Black history as well.

“I went to a predominantly Black elementary school that was mixed with mainly Asian children,” Broussard said. “We had very few white kids in the class. I went to a predominantly Black junior-high and high school. That was when I first became exposed to what we would call Black history today. Much of it was just reading on my own.”

With the odds against him, Broussard credits his ability to succeed to the many mentors he encountered throughout his life. They pushed him to reach his full potential academically and beyond.

“I was very fortunate to connect with some mentors. My mentors were teachers and professors,” Broussard said. “They encouraged my interest in [Black history], so I would occasionally give talks or write papers, and attend conferences that students went to where we talked about Black history. I had a couple of teachers who believed in me more than I believed in myself.”

One of his biggest role models was his mother. Broussard’s mother grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, for most of her childhood and migrated west during World War II. When she arrived in San Francisco, her education was so advanced that she was able to graduate two years early at the age of 16. She then attended San Francisco City College for a year and became a typist. Her mother, Broussard’s grandmother, had only received an eighth-grade education. Broussard’s mother and grandmother ingrained into him that an education would give him more opportunities. He was encouraged to read whenever he could and to participate in academic activities.

“My mother and my grandmother were extremely supportive of my education,” Broussard shared. “They saw it as my ticket out of poverty. If we wanted any kind of future, we had to educate ourselves. That’s what every Black parent told every Black kid of my generation. Education was the one thing that white people could not take away from you.”

In 1968, his senior year of high school, recruiters from colleges throughout the San Francisco Bay Area began visiting local high schools looking for promising black and brown students and convincing them to apply to well-renowned schools like UC Berkeley or Stanford. Broussard was set on going to San Francisco State. His goal at that time was to be a high school history teacher because he had excelled in his social studies and history classes. His teachers, mentors, and role models were the ones encouraging him to go even further.

Broussard ignites the passion he had for Black history in his students at Texas A&M. So far, two of his former students are Pulitzer Prize-winning authors.

“It never occurred to me that I had the grades or the ability to actually go to one of the top schools in the country,” Broussard said. “I applied to Stanford, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, and other places. I got accepted to all the schools I applied to. When I got admitted to Stanford, I got admitted on a full-ride scholarship, much to my surprise.”

Broussard attributes his motivation to further pursue his passions to his mother, grandmother, teachers, and other mentors he had along the way.

“Never underestimate the power of a mentor over the life of another person,” Broussard said. “Sometimes they can shine a light in a new direction that you might not see at that time, especially as a young person.”

Broussard was a part of the largest class of Black students during his time at Stanford. About 50 to 60 Black students were in his class and he thanked the Black students before him for that.

“The increase in the number of Black students on Stanford’s campus was because of the pressure Black students who preceded us placed on the administration,” Broussard explained. “In some cases, they sat in administration buildings and they pressured the administration in various kinds of ways. This all grew out of the civil rights movement, particularly the radicalization of Black students on college campuses. Had it not been for that type of pressure, I seriously doubt that those universities would have opened their doors in any significant way to Black people.”

Broussard took his first official Black history course as an undergrad at Stanford.

“The first Black history course was not available at Stanford until my second year,” Broussard said. “I had a very good experience at Stanford and it felt welcoming. There was a Black community you could connect with on campus if you wanted to. We had a very strong Black student organization on campus.”

“Never underestimate the power of a mentor over the life of another person,” Broussard said.

Broussard’s experience at Stanford further ignited his passion to teach Black history to future generations. He received his master’s degree and Ph.D. in history from Duke University, then taught as a visiting professor at the University of California Davis for one year. He also taught as a visiting professor at the University of Kentucky for one summer. He took on a tenure position in history at a small college in Colorado for a total of four years. He left Colorado for Southern Methodist University in Dallas where he was director of the African American studies program and also taught in the history department. Then Texas A&M came calling.

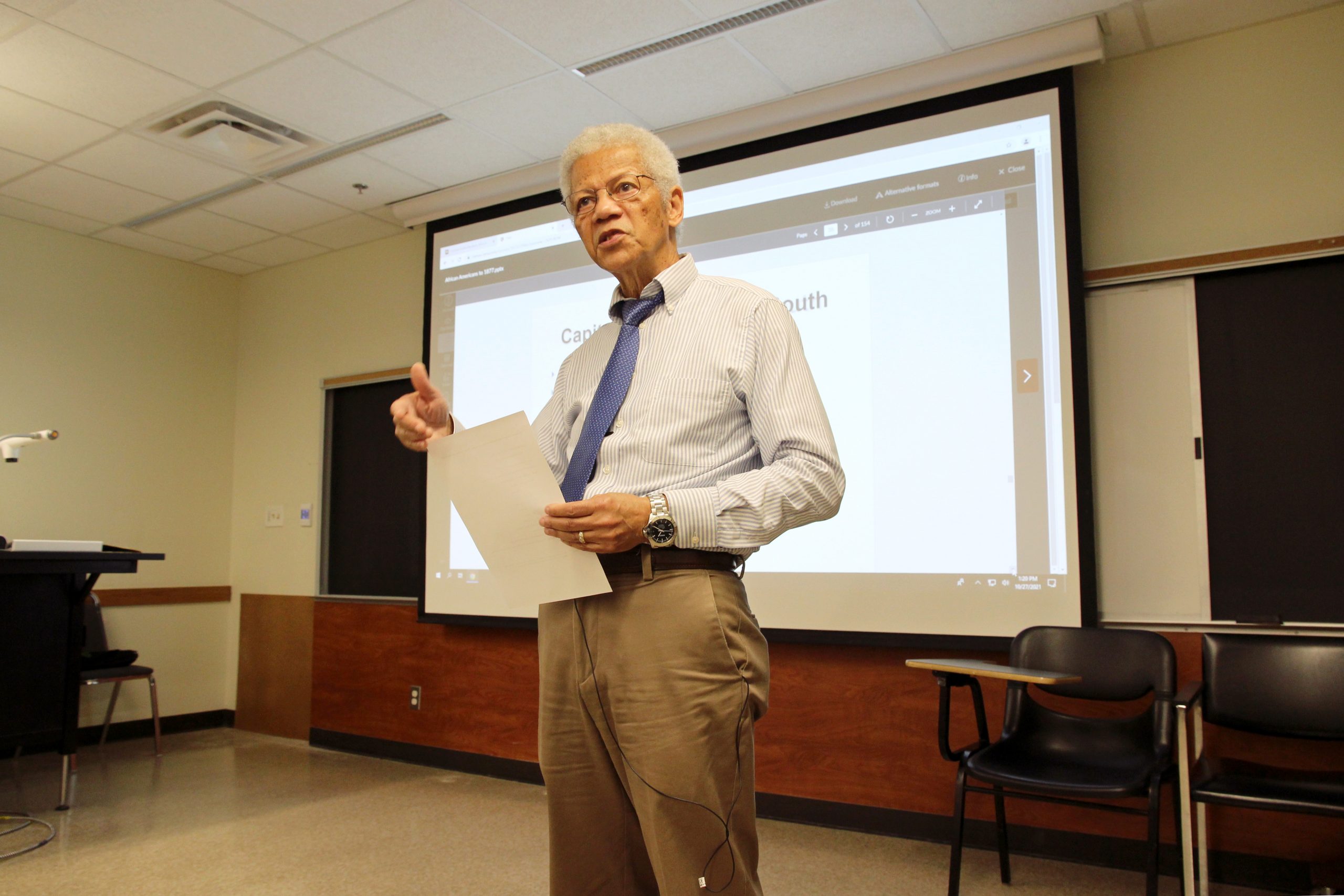

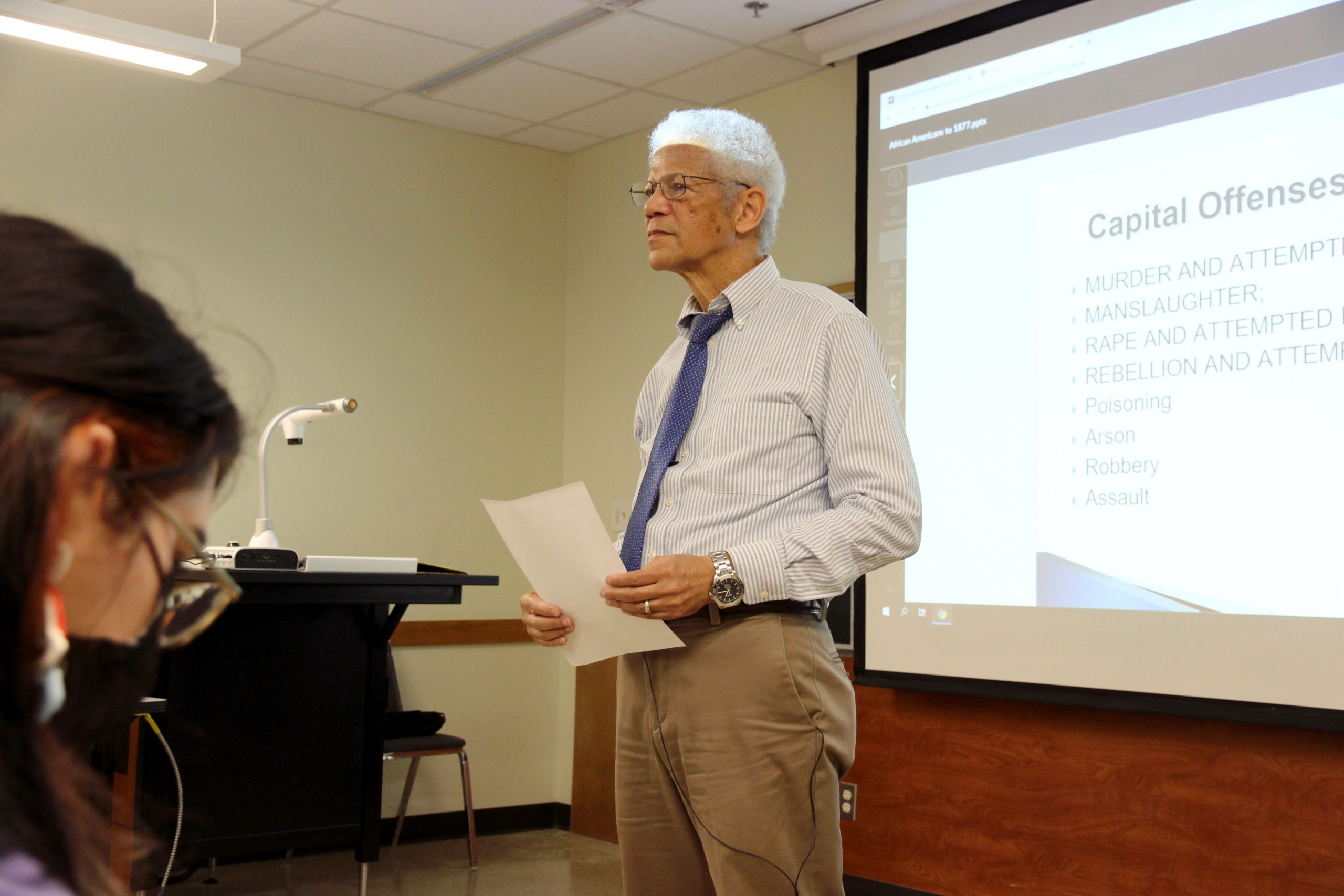

“I came down in ‘85 and offered the first courses in black history,” Broussard said. “I’ve been here ever since. I’ve also taught at the Qatar campus of Texas A&M.”

Establishing a new curriculum for a course that had not been taught at Texas A&M before was not easy.

“They had never hired anyone to teach Black history and there was no Black history course on the books,” Broussard explained. “I put the first two courses on the books and I had to slowly build up the enrollment. The big difference then was that my classes were predominantly Black students. They went to about 50/50 after a couple years and today, they are about 80 percent white and Latino while there are only 20 percent Black students. The racial composition has shifted entirely.”

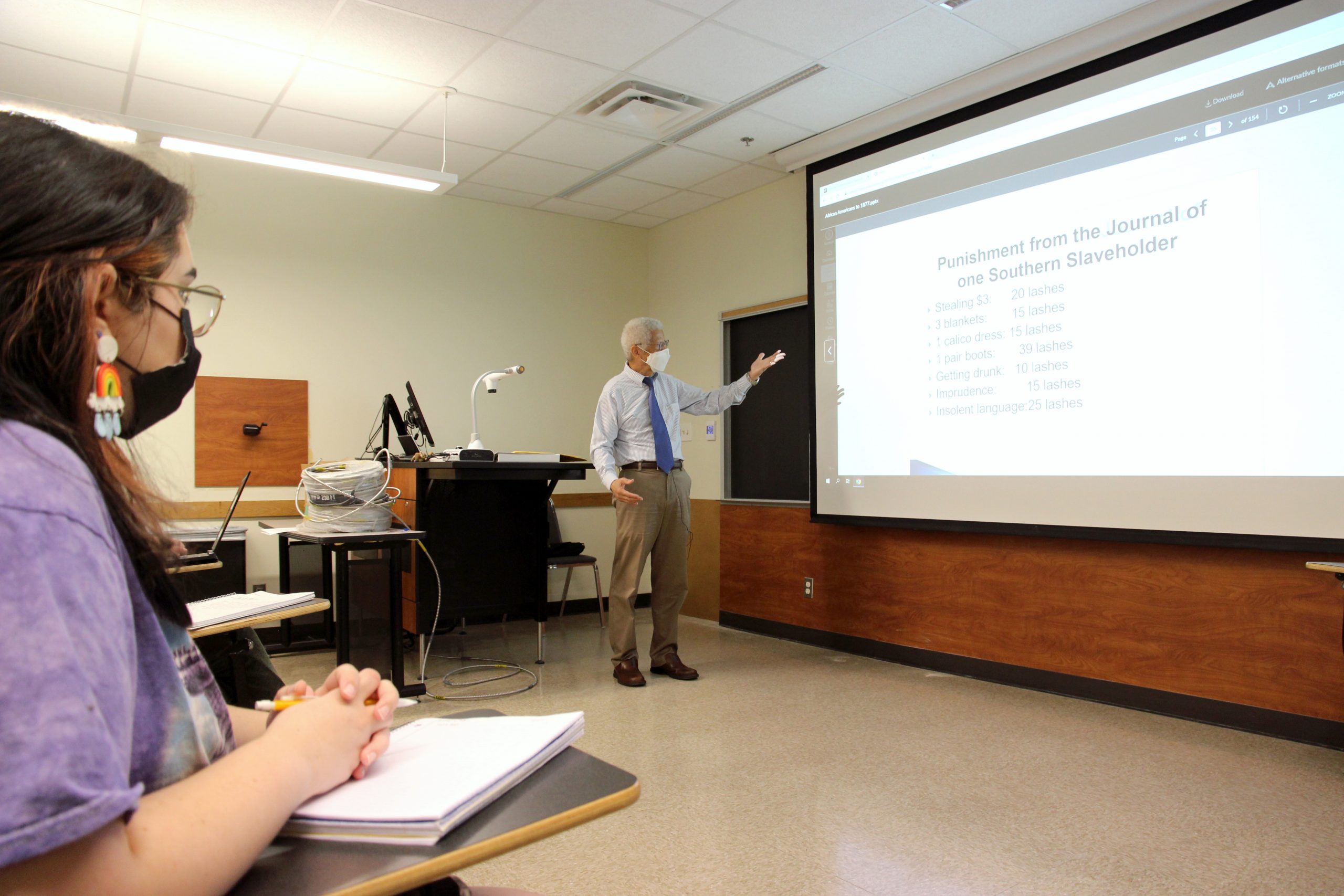

Now, Broussard is igniting the passion he had for Black history in his students. He has a special talent for developing young minds into talented historians. So far, two of his former students are Pulitzer Prize-winning authors.

“I have a dozen or so graduate students, Black and white,” Broussard said. “I’m very proud that every graduate student that I have worked with finished the program and got an academic job. That is quite unusual for a place like Texas A&M. They’re not all teaching Black history, but most of them are. That’s another way to spread what I do and my love for Black history as well. My main motivation is to continue to impart my love for what I do but also teach as many people as possible about the Black experience and the diaspora as well.”

Broussard came to Texas A&M University in 1985 and began offering the first Black history classes to students.

Broussard attributes his means to research and teach a subject that he is passionate about to the College of Liberal Arts. He said the college has supported his academic projects by providing research funding and has given him the time he needs to write scholarly articles. He also said along with all of the things the college has provided him, it provides his students an education unlike any other.

“Liberal arts is the heart and soul of the university,” Broussard said. “The humanities are absolutely instrumental in teaching generations of students to think about their place in the world and their place in society. Humanities teach us about ourselves and teach us about our relationships with each other. God help the university that relegates the liberal arts to a secondary role.”

Black history is a part of U.S. history. Understanding not only the injustices Black people have faced, but the overall history of people of African descent is vital for social change and social progress. Black or not, everyone should learn Black history.

“Black people have been a part of this society from the very beginning,” Broussard said. “They arrived 12 years after the first colony was founded, they were the earliest pioneers in the society, they helped build the society. They have been a vital part of this society. They have fought in every war and they have participated in every major military campaign. They sacrificed their lives even though they have been relegated to second class citizens. Black people are Americans and their history has been slighted and ignored for such a long time. I think it’s time, and the time has long passed, for it to be told.”