CRL Reports: Conservation of Ceramic Firepots

Mombasa, Kenya Project

Institute of Nautical Archaeology

Throughout each year, the Conservation Research Laboratory conserves material from a number of different archaeological projects. The purpose of these CRL reports is to showcase the conservation procedures used to treat some of the more interesting archaeological material. The conservation of ceramic firepots from a 17th-century Portuguese ship is showcased in this report. The Santo Antonio de Tanna wrecked in Mombasa Harbor, Kenya, in 1697. It was excavated by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

CERAMIC FIREPOTS

The Oxford Universal Dictionary on Historical Principles (1955:703) defines a firepot as “An earthen pot filled with combustibles used as a missile.” A more complete description is found in a 16th-century text:

Make great and small earthen pottes which must be but half baked, and like unto the picture in the mergent . . . . Fill every of those pottes halfe with grosse gunpowder pressed downe harde, and with one of the five severall mixtures next following in this Chapter, fill up the other half of those pottes: This done, cover the mouth of every potte with a peece of canvasse bound hard about the mouth of the potte, and well imbrued in melted brimstone. Also tie round about the middle of every potte a packthreed, and then hang upon the same packthreed round about the potte so many Gunmatches of a finger length as you wil, & when you wil throe any of these pottes among enemies, light the same gun-matches that they may so soone as the potte is broken with his fall uppon the ground, fire the mixture of the potte. Or rather put fire to the mixture at the mouth of the potte, & by so doing make the same to burn before you doe throe the potte from you, because it is a better and more surer way than the other: I meane than to fire the said mixture after the potte is broken with burning gunmatches. Moreover this is to be noted, that the small pottes do serve for to be throne out of one shippe into an other in fight uppon the sea, and that the great pottes are to be used in service uppon the lande for the defence of townes, fortes, walles, and gates, and to burne such things as the enemies shall throe into ditches for to fill up the same ditches, and also to destroy emenies in their trenches and campes

(after Lucar 1588, cited in Martin 1994:207-217).

Firepots as incendiary weapons. Source: Biringuccio 1540

Ten firepots were found on the Santo Antonio de Tanna that fit the above description. They are poorly fired ceramic vessels that would have been filled with a combustible material and then either thrown by hand, slung in an attached lanyard, or delivered by sling (Darroch 1986:86; Martin 1994:210).

Similar incendiary devices are shown at right in a wood cut by Biringuccio 1540.

See below for other examples of firepots.

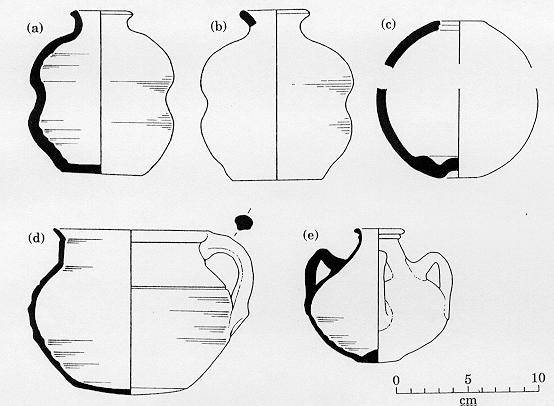

Ceramic firepots from (a) La Trinidad Valencera, (b) Church Rocks wreck, (c) Dudley Castle, Worcestershire, (grenade form), (d) La Trinidad Valencera (possible firepot), and (e) Santo Antonio de Tanna.

Source: Martin 1994:Figure 1

Contemporary representations of firepots (not to same scale): (a) from 1588, (b) from 1598, (c) from 1571, (d) from 1588, (e) from 1628 (this is a close parallel to the Santo Antonio de Tanna example), (f) from 1571.

Source: Martin 1994:Figure 2

From these examples, it would appeart that firepots are rather common in the 16th century. As Martin (1994:211) notes, “by the mid 17th century, ceramic firepots had largely been superseded by explosives grenades of cast iron or glass.”

Following this, it is interesting that ceramic firepots were recovered from a late 17th-century French ship, the Belle, which wrecked in Matagorda Bay, Texas, in 1687. An image of one of these firepots appeared on the April 24, 1997, web page sponsored by the Texas Historical Commission. From the accompanying image and caption, it appears to have been a much more evolved form than those described above. It has a wooden stopper, and in addition to the combustible material, an armed cast-iron grenade with a separate wooden fuse was found inside. No other pots have so far been found that has this extra explosive. How common these were in the late 17th century, or how effective they were, is not known, since the specimens from the Belle are the only known examples of their kind.

CONSERVING EARTHENWARE FROM A MARINE ENVIRONMENT

When a ceramic object is recovered from an archaeological site, it is always sketched and photographed in the condition that it arrives at the laboratory. Pertinent observations are also noted at this time. If, for example, any residues are present on the object, it is important to know the nature of this material. In the case of ceramic firepots, it is useful to have as a starting point a knowledge of the ingredients of the incendiary charges. Sixteenth-century recipes include various amounts of gunpowder, saltpeter, sulfur, varnish, charcoal, stone oil, green coperesse, assa fetida, arsenic, pitch, and gum (cited in Martin 1994:209).

The firepots from the Santo Antonio de Tanna are made of low-fired earthenware and thus are very porous. After they were mechanically cleaned of encrustation, they were, therefore, rinsed extensively to remove any chlorides they may have absorbed from the marine environment. The rinsing process is simple: tap water was continuously run through a vat containing the objects (approximately five of which are intact) until the salt level in the pieces was brought down to the level of the tap water. The objects were then thoroughly rinsed using rain water before being put through several baths of de-ionized water. They were dehydrated and consolidated with a dilute solution of polyvinyl acetate dissolved in acetone. For most earthenware, this impregnating/sealant coat of either polyvinyl acetate or Acryloid B-72 is necessary to keep the friable surfaces from abrading. The sealant is best applied by immersing the vessel or sherd in a bath of the resin. Even more effective is to apply the resin under low vacuum.

Once all the component materials were conserved, the firepots underwent final documentation, which included an array of photographs, both black-and-white and color, detailed drawings, measurements, and relevant research notes.

It should be noted that rain water is used extensively at CRL. In fact, our normal rinsing procedure is to use tap water first, followed by rain water, followed by water from a reverse osmosis system, followed by final baths of de-ionized water. In order to get maximum production from the de-ionizing cartridges, it is the water from the reverse osmosis system (rather than tap water, which contains more soluble salts) that is used to produce the de-ionized water. De-ionized water is expensive, and we have found this procedure saves a considerable amount of money. In any project where extensive rinsing of large volumes of artifacts is required, CRL suggests using this rinsing process.

References:

- Biringuccio, V. 1540. Pyrotechnica. Venice.

Darroch, A. C. 1986 The Visionary Shadow: A Description and Analysis of the Armaments Aboard the Santo Antonio de Tanna. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station.

Martin, Colin J. M. 1994 Incendiary Weapons From the Spanish Armada Wreck La Trinidad Valencera, 1588. The International Journal of Nautical

Archaeology 23(3):207-217.

Lucar, C.

1588 Tartaglia’s Colloquies and Lucar Appendix. London.

Onions C. T.

1955 The Oxford Universal Dictionary on Historical Principles. Oxford University Press, Amen House, London.

Piercy, R. C. M.

1977 Mombasa Wreck Excavation: Preliminary Report. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 22:257-265.

Texas Historical Commission

1997 La Salle Shipwreck Project Photo Album 59. April 24, 1997. World Wide Web, URL http://www.thc.state.tx.us/belle/4-24/photo59.htm

- Citation Information:

Donny L. Hamilton

1997, Ceramic Firepots, Conservation Research Laboratory Research Report #1, World Wide Web, URL, https://liberalarts.tamu.edu/nautarch/crl-reports-conservation-of-ceramic-firepots/, Nautical Archaeology Program, Texas A&M University

E-mail: dlhamilton@tamu.edu