Lake Champlain Projects

Excavation and Survey: 1980-present

Project Directors: Kevin J. Crisman, Arthur B. Cohn

Lake Champlain, the ribbon of fresh-water extending along the state’s western boundary with New York, is one of the best locations on this continent for studying the past 300 years of inland water transportation. The lake’s rich archaeological heritage can be attributed to two factors: its strategic location between the Hudson and St. Lawrence rivers, and the cold, dark, preserving conditions beneath the surface of the water.The maritime history of Lake Champlain can be divided into three eras: the era of military struggles and naval squadrons, the era of commerce and merchant fleets, and the era of recreational boating. The first period essentially began with the shot fired by Samuel de Champlain at a band of Iroquois warriors on July 29, 1609. Over the next one hundred and fifty years the skirmishing between Native Americans was transformed into a contest for the North American continent between France and England, a contest that culminated in General Jeffrey Amherst’s invasion of French-controlled Lake Champlain in 1759 and conquest of Canada in 1760.

Lake Champlain, the ribbon of fresh-water extending along the state’s western boundary with New York, is one of the best locations on this continent for studying the past 300 years of inland water transportation. The lake’s rich archaeological heritage can be attributed to two factors: its strategic location between the Hudson and St. Lawrence rivers, and the cold, dark, preserving conditions beneath the surface of the water.The maritime history of Lake Champlain can be divided into three eras: the era of military struggles and naval squadrons, the era of commerce and merchant fleets, and the era of recreational boating. The first period essentially began with the shot fired by Samuel de Champlain at a band of Iroquois warriors on July 29, 1609. Over the next one hundred and fifty years the skirmishing between Native Americans was transformed into a contest for the North American continent between France and England, a contest that culminated in General Jeffrey Amherst’s invasion of French-controlled Lake Champlain in 1759 and conquest of Canada in 1760.  Peace on Champlain’s waters was short-lived. The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 brought eight years of renewed conflict and, in 1776, the Battle of Valcour Island, where the patriot-traitor Benedict Arnold managed to successfully delay a British invasion of the rebelling colonies. The settlement and stirrings of industry and commerce that followed in the wake of the Revolution were interrupted by yet a third conflict on the lake’s waters, the War of 1812. Although relatively brief, this war witnessed U.S. Navy Commodore Thomas Macdonough’s victory after a desperate naval battle on the placid waters of Plattsburgh Bay. The conclusion of the war in late 1814 also marked the end of the 200-year era of warfare on Lake Champlain.

Peace on Champlain’s waters was short-lived. The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 brought eight years of renewed conflict and, in 1776, the Battle of Valcour Island, where the patriot-traitor Benedict Arnold managed to successfully delay a British invasion of the rebelling colonies. The settlement and stirrings of industry and commerce that followed in the wake of the Revolution were interrupted by yet a third conflict on the lake’s waters, the War of 1812. Although relatively brief, this war witnessed U.S. Navy Commodore Thomas Macdonough’s victory after a desperate naval battle on the placid waters of Plattsburgh Bay. The conclusion of the war in late 1814 also marked the end of the 200-year era of warfare on Lake Champlain. The nineteenth century was to be Lake Champlain’s “Golden Era” of waterborne commerce. During this period the lake churned with the wakes of hundreds of merchant vessels of all descriptions: steamboats, canal boats, scow ferries, merchant sloops and schooners, horse ferries, tugboats, and untold numbers of lesser craft. Throughout most of the nineteenth century the lake was also on the cutting edge of new maritime technology, the most spectacular and best-remembered being the smoke-belching steamboats that carried tourists, immigrants, businessmen, and families up and down the length of the Champlain Valley. Of greater economic importance, although perhaps less-remarked, were the canals, an advance in technology that joined Champlain’s waters with the Hudson River in 1823 and the St. Lawrence River in 1843. The Champlain and Chambly canals provided a cheap, dependable connection between Vermont and the rest of North America, and floated an incredible range of materials in and out of the region, including coal, timber, iron ore, grain, hay, stone, and manufactured goods.

The nineteenth century was to be Lake Champlain’s “Golden Era” of waterborne commerce. During this period the lake churned with the wakes of hundreds of merchant vessels of all descriptions: steamboats, canal boats, scow ferries, merchant sloops and schooners, horse ferries, tugboats, and untold numbers of lesser craft. Throughout most of the nineteenth century the lake was also on the cutting edge of new maritime technology, the most spectacular and best-remembered being the smoke-belching steamboats that carried tourists, immigrants, businessmen, and families up and down the length of the Champlain Valley. Of greater economic importance, although perhaps less-remarked, were the canals, an advance in technology that joined Champlain’s waters with the Hudson River in 1823 and the St. Lawrence River in 1843. The Champlain and Chambly canals provided a cheap, dependable connection between Vermont and the rest of North America, and floated an incredible range of materials in and out of the region, including coal, timber, iron ore, grain, hay, stone, and manufactured goods. The third era in the lake’s written history began with the introduction of the railroad to the Champlain Valley in the late 1840s. This new form of transportation initially served as a complement to the existing passenger trade on the lake, but with the introduction of new rail lines and more miles of track the use of Lake Champlain as the region’s primary artery of transportation gradually tapered off. Steamers and canal boats would continue to navigate the lake and canals well into the twentieth century, but by the end of the nineteenth the railroad’s primacy in the passenger- and freight-hauling business was complete. The twentieth century has seen Lake Champlain emerge, after a period of disinterest and neglect, as a center for recreation, for fishing, for swimming, and especially for sail and motor boating.

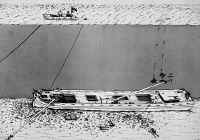

The third era in the lake’s written history began with the introduction of the railroad to the Champlain Valley in the late 1840s. This new form of transportation initially served as a complement to the existing passenger trade on the lake, but with the introduction of new rail lines and more miles of track the use of Lake Champlain as the region’s primary artery of transportation gradually tapered off. Steamers and canal boats would continue to navigate the lake and canals well into the twentieth century, but by the end of the nineteenth the railroad’s primacy in the passenger- and freight-hauling business was complete. The twentieth century has seen Lake Champlain emerge, after a period of disinterest and neglect, as a center for recreation, for fishing, for swimming, and especially for sail and motor boating. The fleets of warships, steamers, merchant ships, and canal boats have long since departed from the surface of the lake, but fortunately for us they have not passed entirely into oblivion. Over the centuries disasters large and small sent scores of vessels to the bottom. Sinkings were occasionally the result of dramatic naval battles or the ever-present hazards of collision, fire, and storm, but the greater number appear to have been the result of decay, neglect, and old-age working on the planks and frames of a wooden hull. Once a vessel went to the bottom, it entered what is essentially a cold, dark vault, ideal for the preservation of wood and other organic materials. Thus, with the passing years the lake bottom has acquired a collection of ships and artifacts, a collection with much to tell us about maritime technology and shipboard life over a span of three centuries.

The fleets of warships, steamers, merchant ships, and canal boats have long since departed from the surface of the lake, but fortunately for us they have not passed entirely into oblivion. Over the centuries disasters large and small sent scores of vessels to the bottom. Sinkings were occasionally the result of dramatic naval battles or the ever-present hazards of collision, fire, and storm, but the greater number appear to have been the result of decay, neglect, and old-age working on the planks and frames of a wooden hull. Once a vessel went to the bottom, it entered what is essentially a cold, dark vault, ideal for the preservation of wood and other organic materials. Thus, with the passing years the lake bottom has acquired a collection of ships and artifacts, a collection with much to tell us about maritime technology and shipboard life over a span of three centuries.

Over the past twenty years researchers working for the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum have been able to locate and study examples of nearly every type of vessel that ever floated upon Champlain’s waters. The many spectacular finds are making it possible to write a new and more detailed history, one that concentrates on the ships and on the people, some famous and many unknown, who sailed upon the “mountain waves” of Lake Champlain.

Over the past twenty years researchers working for the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum have been able to locate and study examples of nearly every type of vessel that ever floated upon Champlain’s waters. The many spectacular finds are making it possible to write a new and more detailed history, one that concentrates on the ships and on the people, some famous and many unknown, who sailed upon the “mountain waves” of Lake Champlain.

(text adapted from Crisman, Kevin J., “Lake Champlain Nautical Archaeology Since 1980,” The Journal of Vermont Archaeology, v.1 (1994)153-166.)