Illuminating Humanities: Hoi-eun Kim

Highlighting Humanities Research and its Impact

Hoi-eun Kim | History

by Jennifer Wells '10

The Glasscock Center is excited to continue its series which highlights humanities research at Texas A&M, and the vital role played by the humanities at the university and in the world beyond the academy.

For this highlight, we invite Dr. Hoi-eun Kim, to tell us about his Glasscock Internal Faculty Residential Fellowship supported by the Glasscock Center.

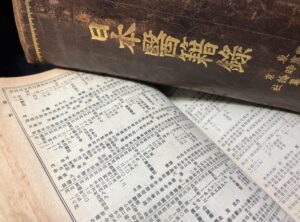

Dr. Hoi-eun Kim, a recipient of a 2023 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Faculty Award, is an Associate Professor in the History Department at Texas A&M University. His research examines modern Germany and modern East Asia, with a focus on transnational exchanges. In 2017, Dr. Kim received an Internal Faculty Fellowship from the Glasscock Center to support his research on Japanese doctors in colonial Korea from 1910 to 1945. He used the Fellowship's funding to comb through medical directories featuring Japanese physicians who had established practices in Korea. With the help of a research assistant in Japan, Dr. Kim cataloged their information into a searchable excel database. Dr. Kim shares, "Glasscock funding was really crucial in getting this project off the ground." In documenting their practice location, birthdate and place, medical school information, licensing details, and specialties, Dr. Kim's findings became the basis for his NEH application.

Dr. Kim's inspiration for this project evolved from lingering questions related to his first book, Doctors of Empire: Medical and Cultural Encounters between Imperial Germany and Meiji Japan (2014). In it, Dr. Kim examines how Japan modernized itself by sending scholars to learn from leading experts around the world. Far from isolated entities, Dr. Kim's investigation illuminates the transnational exchanges that occurred during this period. As part of this process, Japanese officials invited German physicians to teach medicine at Tokyo Medical School (now the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Tokyo) in the 1870s, initiating a lengthy exchange between the two. Germany's influence was so strong that only defeat in World War II ended the Japanese practice of writing medical dissertations and articles in German.

Dr. Kim builds on his first book by charting the career paths of Japanese doctors after acquiring a license to practice. He uses underexplored sources—published physician directories—to trace how the medical professionals crisscrossed the Japanese Empire and beyond.

As with other careers, like law and education, the turn of the twentieth century witnessed the rise of professionalization. Hopeful doctors had to demonstrate competency by graduating with advanced degrees, passing comprehensive exams, and adhering to universal standards. The rise of medical directories reflected this move toward professionalization, with doctors attempting to assert their legitimacy through self-paid advertisements. And while intended for potential patients seeking medical care, doctors were their most ardent consumers. (It's not a stretch to imagine plucky young physicians thumbing through freshly printed directories aiming to scoop out the local competition.)

After sifting through the data, Dr. Kim discovered something startling. Classic interpretations tend to portray Japanese doctors as one-dimensional "tools of the Empire," depicting them as nefarious beings who used their standing as medical experts to perpetuate false notions of the Empire's superiority to justify colonization. And although Dr. Kim's research acknowledges their involvement in imperialism, it also indicates that other factors influenced their decision-making.

Specifically, he underscores how profit prompted most to migrate to Korea. Dr. Kim notes that scholars frequently dismiss the pecuniary impulses of medicine. But, by the 1920s, doctoring was well on its way to becoming a full-fledged business. With its high Japanese expatriate population eager for biomedicine-trained physicians, Korea seemed like the land of opportunities for Japanese physicians hoping to establish themselves. Dr. Kim states that by following the money, we can better understand Japanese doctors as actual people with motivations beyond imperialism.

His research also reveals that for native Koreans, visits to medical clinics were few and far between. Due to cost restrictions and language barriers, most opted for self-medication. Dr. Kim notes that thousands of peddlers roamed Korea in the 1920s and 1930s, promising miracle cures for cheap. Pregnant Koreans also preferred local midwives to foreign practitioners. In addition, practitioners rarely remained in rural areas for long and were apt to settle in bustling cities as soon as they could afford it. Thus, while Japanese doctors practiced medicine in Korea, their direct involvement with the local populace was often fleeting.

Dr. Kim hopes his research restores the lives and experiences of those often reduced to tropes in traditional accounts. In detailing the collective biographical characteristics of Japanese doctors in colonial Korea, Dr. Hoi-eun Kim injects existing accounts with a healthy dose of nuance.

You may find his article "Adulterated Intermediaries: Peddlers, Pharmacists, and Patent Medicine Industry in Colonial Korea," which won the 2020 Philip Scranton Best Article Prize from the Business History Conference, here.

In addition, the College of Arts and Sciences recently featured information about Dr. Kim's scholarship, here.

An image of a directory featuring Japanese physicians.