History Peeps: Ian Seavey, Ph.D. Student

A Florida native with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Tampa, Ian Seavey remembers the culture shock he experienced when he first saw Texans on campus in Western boots and cowboy hats. “I really thought that was just a funny stereotype,” the graduate student relates. “I had no idea anyone actually still dressed like that today.” In the four years since then, Seavey has become something of an expert on another Texas phenomena: hurricanes. Specifically, his research examines the municipal and federal responses to the 1899 San Ciriaco Hurricane in Puerto Rico and the 1900 Great Storm of Galveston.

A Florida native with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Tampa, Ian Seavey remembers the culture shock he experienced when he first saw Texans on campus in Western boots and cowboy hats. “I really thought that was just a funny stereotype,” the graduate student relates. “I had no idea anyone actually still dressed like that today.” In the four years since then, Seavey has become something of an expert on another Texas phenomena: hurricanes. Specifically, his research examines the municipal and federal responses to the 1899 San Ciriaco Hurricane in Puerto Rico and the 1900 Great Storm of Galveston.

These back-to-back disasters devastated two previously vibrant Gulf communities and caused as many as 16,000 fatalities. Although he had known about both events since taking an undergraduate course on natural disasters, the once-in-a-century hurricane season of 2017 confirmed Seavey’s interest. Over the course of that autumn five years ago, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria devastated Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico respectively. They led Seavey to want to learn more about American disaster response, including the ways that politics influenced recovery and rebuilding.

Seavey’s findings will appear in the Journal of Advanced Military Studies later this spring under the title, “A Tale of Two Storms: Progressive Era Disaster Relief in Puerto Rico and Texas, 1899-1900.” In it, he argues that the 1899/1900 hurricane relief efforts led to innovative administrative reforms that made rebuilding efforts more efficient but also reinforced existing power structures. The San Ciriaco Hurricane hit Puerto Rico only a year after the United States had begun administering the island in 1898. Seavey’s work shows that U.S. military governor Brig. Gen. George Davis saw the Hurricane as an opportunity to demonstrate the benefits of American rule compared with the inept Spanish colonial government. Davis implemented the island first relief program following 400 years of neglect by Spain. He encouraged growers to shift from coffee to sugar production since the latter crop was more resistant to hurricane winds. Yet, Davis also chose to funnel this aid through local plantation owners. Without strong oversight, many landowners stole the funds. Others distributed the aid intended for workers, but only to solidify their place at the top of the island’s quasi-feudal social structure.

Similarly, the municipal government of Galveston responded to the Great Storm of 1900 by reorganizing its corrupt city council into a city commission. Free of gridlock, the commission government built a ten-mile-long sea wall and raised all of Galveston 17 feet. On the other hand, it also gerrymandered the new larger electoral districts to exclude Galveston’s African American voters. After this, the commission would be all-white until the city government was reformed again in 1960.

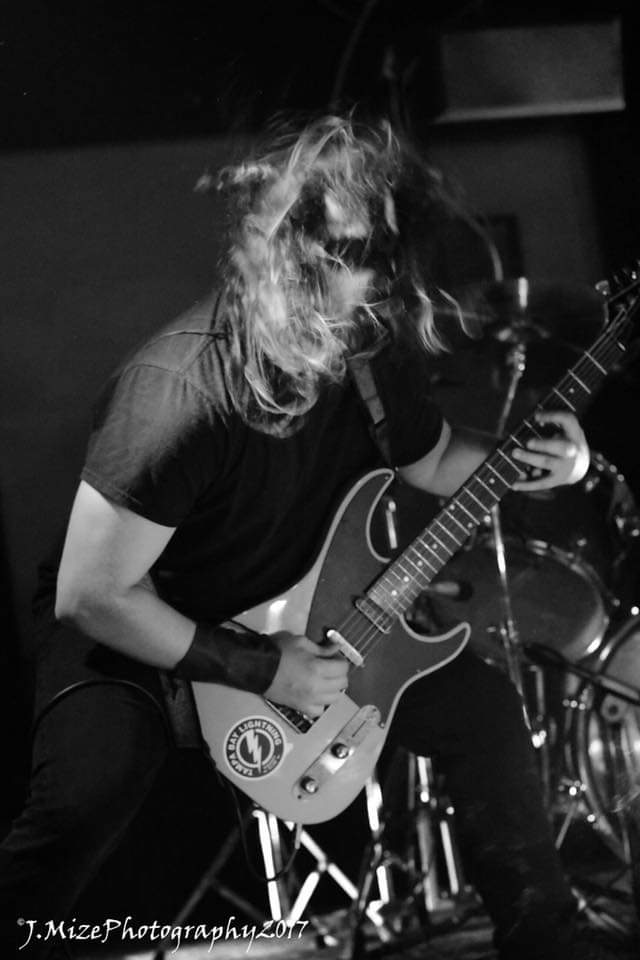

Although Seavey is hard at work on his dissertation this semester, he still finds time to captain the History Department’s official softball team in the College Station Rec Leagues. The team that Seavey co-founded last semester, had a respectable 1-1 record at the time of publication. According to at least one fellow graduate student, Seavey is “the best shortstop in the entire Rec League, hands down,” and is famous for his play-ending centerfield catches. He also writes music and plays in a local metal band.

To what historical figure would he like to say “howdy” if given a chance? Famed boxer Muhammed Ali “for so many different reasons” would be Seavey’s first choice. “For one thing, he was one of the first big-time athletes to leverage his fame into awareness of other important issues like Civil Rights and the draft resistance movement. But he did that for so many different categories too – he was also an advocate for religious freedom as a Muslim. And he was just a great boxer, too.”

(Patrick Grigsby ’27)